Chapter 12 of 13

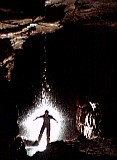

Water can present a hazard underground, not just from the dangers of flooding, but more commonly from the cold. Most cavers choose to wear wetsuits in cold water as the wetsuit uses the water to create insulation, a system that works very effectively but only if the caver does not stay still for too long. We were heading for a trip into Maytime, Agen Allwedd to see the large passages that were on view there. I have been into the cave several times before and was quite aware of what to expect. The walking sized entrance series, the easy walking main passage then a few long crawls to Maytime.

I knew that Maytime contained several sections of deep water, so I decided to wear my wetsuit, as I had no intention of freezing myself in the cold river that runs through the cave. No-one else was worried so they all wore a fleece undersuit and a water resistant oversuit.

We headed into the cave with me walking like an elasticated penguin and the others walking in a way reminiscent of humans. A wetsuit is always more tiring to wear as it is a form of rubber and so resists all movements, attempting to spring back into its natural shape. Still, I was tough enough and had enough stamina so that was by no means a problem. I would just get a better workout.

We soon reached the first of the crawls. I was overheating slightly in my dry wetsuit and was sweating. At this point, I am sure that many cavers would cringe, as they know what is going to happen. I did not. Southern Stream Passage was lower than I had expected and after about one kilometre, I was feeling uncomfortable. My wetsuit war rubbing my groin and making the skin very sore. We continued through the long sandy crawls of Resurrection Series and finally reached the crawl into Maytime. We were all very surprised by the sight that greeted us. A few stalactites covered with stunning displays of helictites, very similar to some seen in the White Company stal formation in Ogof Daren Cilau. This was very unusual for Agen Allwedd as it is almost devoid of stal formations throughout its length and these were exceptionally beautiful.

Now very sore, I was eager to get into the water and sooth the wetsuit rash I had developed. Sending someone in first - yes, I don't like water that much - I quickly followed. Nice and cold. Very pleasant. Following the stream down a few cascades, we saw some more unusual formations. High in the roof, a collection of very thick 'straw' stal formations hung on a slant instead of directly downwards. We soon reached the sump where we turned around to head out. I was enjoying being in the water but I knew the worst was to come.

Now quite wet, my wetsuit would rub far more than it had on the way in, unless I could continually immerse myself in water. Sadly, Southern Stream contains only a trickle of water, and I had to suffer. By the time we got to the end of the Main Passage, I was almost in tears with pain and ran down to the streamway to soak. When we finally reached the car, I took off the wetsuit to asses the damage. My groin looked red and was missing a lot of skin. I walked with my legs apart for a few days, whimpering with every movement. To this day, several years later, I still have scars from that.

It did not put me off that cave through, although I have never worn a wetsuit in there since. I did have another few memorable trips into the cave, one of which is worth a definite mention. It was in the depth of winter, and snow was covering the mountain side. We walked along the derelict tram road to the entrance, admiring the view of the white snow against the black of the quarry face that had originally cut into the cave. Within the first hundred metres of the cave there are two puddles in the floor, where the roof is so low that the only way through is to lie in the puddles.

With the cold outside, these puddles were made with meltwater from the snow and the draught blowing into the cave was providing a healthy wind chill factor, dropping body temperatures rapidly. I have been into Draenen when the draught was cold enough to form icicles in the entrance but this draught felt far colder. We hurried through the cave trying to get warm. We could not move too fast though as there is a large bat colony that hibernates in the cave and many of them choose to sleep just where you would want to put your hands.

Once into the Main Passage, we hurried along and managed to regain a normal body temperature, taking a lot of time looking around. It was when we started back out that things started to get too much. The draught in the entrance series was bitterly cold, this time blowing into our faces and quickly lowering the temperature of the water soaked up by our undersuits. We were warm enough from the caving though and the cold did not present too much of a problem. This was all to change when we reached the puddles near the entrance. On the way in, some of us had the strength to push ourselves off the floor, managing to keep dry to a some extent. On the way out, cavers are too tired for this to be possible.

Tired from the caving, we all lay in the water and wriggled through. Now the draught was becoming a problem. The water was at about 0°C and was excruciatingly cold. The draught could have blown it into icicles on our oversuits if we stopped moving. Outside, we shivered our way back to the car, me suffering more than most. The walk around the mountain is a couple of miles long and we could not hurry, as the slope below us was very steep and a slip here could land you a hundred metres below. One caver who had done this was lucky enough to be stopped by a rock pile about twenty metres down. Some of us did slip over on the way back, but we all arrived back at the cars one piece.

By that time our hands were freezing. I had to have my dad help me by rubbing my hands and breathing on them to warm them back up. It was not very successful. The only movement I could manage was to move the tips of my fingers by about half of a centimetre. That was all I could do in the cold. The pain in my hands as they warmed up felt like fire. It was as if I had put them into a fire and was slowly roasting them. This certainly gives you a lot of respect for people like Eskimos who live in these conditions their whole lives.

Had I been warmer, I might have attempted the Eglwys Faen challenge. Eglwys Faen is a small cave about one kilometre long on the path to Agen Allwedd. It was obviously once a part of the great Llangatwg Master System comprising Agen Allwedd, Ogof Daren Cilau and Ogof Craig A Ffynnon, which are now separated by chokes. It has seven entrances for normal cavers and a couple more for very small cavers. The main entrance lies up a slope at the Agen Allwedd end of the cave, and the Waterfall Entrance lies up a slope at the other. The challenge begins after a trip into Agen Alwedd.

Walking up the steep slope, the timer starts at the main entrance. Tired from the trip to Agen Allwedd and the walk up the slope, the caver must descend into the cave so overused by novices. The entrance opens out directly into a fragment of huge passage, probably related to the Main Passage in Agen Allwedd. Blinded from the light outside and the sudden blackness of the large passageway, the caver stumbles into a passage on the left. This narrows down and the caver regains their vision. Ahead, the passage twists, turns and climbs, passing under a skylight entrance. The way on shrinks down to a crawl and soon, a climb down leads to two flat out crawls. Taking either, a larger passage is reached and followed to the left. A short crawl emerges under the waterfall where a climb ends on the top of the slope down to the path again. It is here that the timer stops. My dad and uncle used to do this twenty years ago, and I intend to carry on the tradition, bringing their time of four minutes down to two and three quarters for a distance of 150 metres. In case you were wondering, that is an average speed of 3 kilometres per hour or 2 miles per hour.

The cold can play quite a big part in caving, and despite what many people think, it is the cold that is the biggest threat underground. A caver with an injury is more likely to die of hypothermia than blood loss. The cave air - in Britain at least - is harsh and unrelenting, usually staying constant, somewhere below 10°C. On the surface, the temperature may vary quite significantly, but the air in the cave still maintains its temperature, unless a draught drags air in from the surface.

We were in Yorkshire for a caving weekend and for one of the trips, we were to visit Hagg Gill Pot, a recent discovery just over one kilometre long. It had been a cold night and the dales were covered in a blanket of snow. The sun was out though and the snow was beginning to melt. As is customary in Yorkshire, cavers park on the road nearest to the cave and change into caving gear outside their cars. The nearest road to this cave lay in a shallow valley that funneled an icy wind along its length.

We got out of our car and the Yorkshire cavers who were leading us into the cave got out of theirs. The next step was to get undressed and change into caving gear. In this cold? There was not even a wall to shelter behind. The Yorkshire cavers got out their caving gear and got undressed, leisurely changing into their gear. They breed 'em 'ard up 'ere!

We got changed, more used to doing so in the comfort of the house and then driving to the cave already in our fleece undersuits. With every breath of the wind, we cringed and cowered behind the boot of the car. They definitely breed 'em 'ard up 'ere!

The entrance pitch was rigged and we descended into the relative warmth of the cave. We followed the stream at the bottom upstream, passing several beautifully decorated sections of passage. Later we headed downstream, taking the inlet before the sump, where there were more stal formations, but not so intricate. On many occasions we were lying in the stream, composed of meltwater from the snow on the surface. I can only assume that the water had been underground long enough to have reached the normal cave temperature, because the effects of the water were nothing like as severe as from the water in Agen Allwedd.

In most Yorkshire potholes, water is all a part of the sport. I have been to many very wet Yorkshire potholes, where abseils beside huge waterfalls dominate the experience. Yorkshire potholers tend not to spend much of their time in contact with the rock and instead can usually be found dangling from their bits of string - sorry, rope - high above the floor. Where I do most of my caving, in South Wales, we hardly have any potholes to dangle around in. Yorkshire potholers wear different clothing; their oversuits are more water resistant but will suffer more from abrasion.

Some of the most popular potholes I have been in are a part of the West Kingsdale Master System, which actually drains both East and West Kingsdale. These potholes are usually rigged as pullthroughs and have several short pitches uniting in a central cave system. It is at the parking places for these potholes that my next short story begins. Picture it if you will.

It is a sunny day. The birds fly past, each one staring at the usual arrivals. One arrival, a beast with four round feet, stops and gives birth to three little beasts, each with two legs, and a couple of other appendages. One such little beast bears a striking resemblance to myself, one to my dad and one to my brother. We are preparing to go caving in Swinsto Hole. My brother and I take off our outer garments, wait until there is no traffic, and quickly replace our normal underwear with that intended for caving. Then, it is our dad's turn. He also removes outer garments and waits for a break in the traffic.

Seizing the moment, he drops his underwear and places it on top of his outer garments in a neat little pile. At that moment, a convention of vintage car enthusiasts, each one over sixty years old - that's the enthusiasts, not the cars - appears as if by magic. Small faces peer out of the windows in horror at the sight that greets them. Aged women cling to their men desperately hoping that they can do something to block out the vision. Back to hell demon! Yes, my dad has inadvertently exposed himself in front of a whole troop of elderly men and women.

In fact he has done this several times by several Yorkshire caves; he has an ability to pick the one moment when it sounds and looks like there is no-one approaching but in actual fact there is a small army of elderly people out for their respective drives in the countryside. The most memorable occasion was after a caving trip. We were getting changed out of our wet caving gear, the sensible ones of us having wrapped towels around ourselves like sarongs. My dad again waited until there was no possibility that anyone could be passing, again picking exactly the wrong moment. Realizing the impending incident, he ran for cover behind the car. Safe at last. Except that my brother's fiancée was sitting in the car at the time and most certainly did not appreciate the intrusion. Again he tried to duck for cover, away from the car, instead showing himself off to the car he had tried to avoid. What a guy!

In South Wales, there are relatively few caves where that could happen as there are almost no caves situated that close to the roads. One exception is Ogof Nant Rhin, whose entrance is situated just below a lay-by on the major A road that runs along the Clydach Gorge. The entrance was excavated from under a pile of spoil tipped down the embankment when the route for the road was cut. It contains three squeezes in the entrance passage, the third of which is nearly half full of water.

I am fairly small, despite appearances. I can fit through an 18 cm (7¼ inch) gap, unless I am using a rack descender in Simpson's Pot, but that is another story. Ogof Nant Rhin did not present a problem at all. I cannot remember exactly who was on the trip here, except that my brother's fiancée was there and I do not think there was anyone else. We had gone in through the entrance, her having no problems at all, being far smaller than me. The cave was quite interesting, with several stal decorations and a small streamway. At the end of the cave, both branches rose to either chokes or narrow rifts.

It was a short trip as the cave is only 350 metres long. We headed out along the walking sized passage. The roof began to lower signifying that the entrance passage was just up ahead. My brother's fiancée went through first, and once through, stood at the entrance to wait for me. I reached the last of the three squeezes, which to me is not really a squeeze, just a small passage. I got half way along the passage and then found I could move no further. My head was at the entrance but I could not move to get the rest of my through it.

I tried to move backwards to un-stick myself from whatever I was stuck on. My boot jammed into a narrow cleft in the floor, the perfect size for my boot. I was using a belt mounted battery, with the cable from that taking the electricity to the light unit on my helmet. As is quite common with this arrangement, the cable had got caught on a rock projection, preventing me from moving further along the passage. The usual response is to flick the cable off the projection either by turning the head quickly or pulling it using the hands. I could not do either in this passage. I had to give up and ask my brother's fiancée to unhook it by reaching around me. My boot was left behind, stuck in the floor so I turned around to pick it up.

This is not the only time I have had to give up. On a trip with my wife and brother into Agen Allwedd, we got to Southern Stream Passage and I decided to go into Sandstone Passage as I had not been there before. Leaving the others behind, I sped along the passage, through the U-bend squeeze half way along. I had told them I would not be long so I turned around before reaching the end.

When I reached the squeeze, I started through and then realized I had lain down on the wrong side as I could not get my foot onto any holds to push myself up the slope. I tried to roll over but the shape of the passage was preventing that, so I tried reversing to roll over. I could not reverse because of the position I was in. After five minutes, I stopped wriggling and lay there. Had I started on my other side, I would have been through in a few seconds. Now I was stuck.

I knew my brother would follow soon if I did not turn up so I began to shout for help, hoping that he would hear me and come to help. There would be no chance of him hearing and all I succeeded in doing was making myself feel stupid. Now determined, I wriggled for a few more minutes, finally managing to get a foot hold and push myself through. Once out of the passage, they both said I was late and they were cold now and I was inconsiderate. I explained what happened and my brother informed me that he would have left it another few minutes before looking for me. I would have been there for over quarter of an hour before he reached me. I do this for fun!