Pant Mawr Pot trip 30/10/2021

Unless otherwise stated, camera, setups, lighting, edits and gallery effects by Tarquin. Modelling and lighting at various points will be Pete Bolt and Jules Carter.

This was only my third trip into this cave, with the first and second being in 1997. It was intentionally visited for the purpose of photography, and there will be a lot of photographs. Oh dear, what a shame.

There had been some very heavy rain for the last two days before our visit, but cavers familiar with the area had assured us that the cave responds rapidly to rain, and by now the water levels should have dropped far enough to allow our visit. In the worst case, we might only get to see about half of it. Nevertheless, the river was running very high, and brought a great deal of fog and atmosphere. There were some residual light scattered rain showers in the surrounding mountains during our visit, but we managed to avoid it all.

View over the upper Tawe valley. Carreg Lwyd crags, Hirfynydd (481 metres), Mynydd Marchywel (418 metres), Cribarth (428 metres), Carreg Goch (558 metres), Garreg Las (635 metres), Fan Hir (761 metres), Cefn Cul (562 metres) and Fan Gyhirych (725 metres).

Modelling by Pete

View over the upper Tawe valley. Carreg Lwyd crags, Hirfynydd (481 metres), Mynydd Marchywel (418 metres), Cribarth (428 metres), Carreg Goch (558 metres), Garreg Las (635 metres), Fan Hir (761 metres), Cefn Cul (562 metres) and Fan Gyhirych (725 metres).

Modelling by Pete Walking into the basin of the Byrfre Fechan. The Nant Byfre flows off to the left, while the Byfre Fechan sinks into the basin. On the left are the flanks of Fan Gyhirych, but the top is hidden some distance away. On the right are the Carreg Cadno outcrops (538 metres).

Modelling by Pete and Jules

Walking into the basin of the Byrfre Fechan. The Nant Byfre flows off to the left, while the Byfre Fechan sinks into the basin. On the left are the flanks of Fan Gyhirych, but the top is hidden some distance away. On the right are the Carreg Cadno outcrops (538 metres).

Modelling by Pete and Jules Striding past the deeply incised sinks at Pwll Byfre. The location of the sink has migrated in the past, and so far all of them have resisted digging.

Modelling by Pete and Jules

Striding past the deeply incised sinks at Pwll Byfre. The location of the sink has migrated in the past, and so far all of them have resisted digging.

Modelling by Pete and Jules The main Pwll Byfre, with a swollen river forming a lake in the main sink. This is the upper end of the Ogof Ffynnon Ddu system, with the known cave ending some distance away to the right.

The main Pwll Byfre, with a swollen river forming a lake in the main sink. This is the upper end of the Ogof Ffynnon Ddu system, with the known cave ending some distance away to the right. Crossing the watershed into Pant Mawr; the big hollow. The cave's stream drains the left edge of the forest, and can produce a surprising amount of water. The entrance can be seen as a dark spot just below the right edge of the trees. Fan Fraith (668 metres), Fan Nedd (663 metres), Fan Llia (632 metres), a distant Cefn yr Ystrad (617 metres) and Carreg Cadno.

Modelling by Tarquin's shadow, Jules and Pete

Crossing the watershed into Pant Mawr; the big hollow. The cave's stream drains the left edge of the forest, and can produce a surprising amount of water. The entrance can be seen as a dark spot just below the right edge of the trees. Fan Fraith (668 metres), Fan Nedd (663 metres), Fan Llia (632 metres), a distant Cefn yr Ystrad (617 metres) and Carreg Cadno.

Modelling by Tarquin's shadow, Jules and Pete The shakehole entrance of Pant Mawr Pot. Despite the name, it is not really a pothole, it is a substantial cave with a single pitch entrance. It is academic as to what constitutes a pothole rather than a cave, but Ogof Draenen has perhaps 100 pitches, but would never be considered a pothole. A typical pothole would need to either consist almost entirely of a vertical system, or have multiple pitches on its primary routes. This is neither. Nevertheless, it starts out as a pitch, and a backup handline is required right from the start to descend into the shakehole.

Modelling by Tarquin's shadow, Pete and Jules

The shakehole entrance of Pant Mawr Pot. Despite the name, it is not really a pothole, it is a substantial cave with a single pitch entrance. It is academic as to what constitutes a pothole rather than a cave, but Ogof Draenen has perhaps 100 pitches, but would never be considered a pothole. A typical pothole would need to either consist almost entirely of a vertical system, or have multiple pitches on its primary routes. This is neither. Nevertheless, it starts out as a pitch, and a backup handline is required right from the start to descend into the shakehole.

Modelling by Tarquin's shadow, Pete and Jules The pitch head begins with a backup, Y-hang, then down to a rebelayed Y-hang at the head of a superb free-hang into the main passage of the cave. The rebelay has a conveniently placed platform of jammed rocks to stand on.

The pitch head begins with a backup, Y-hang, then down to a rebelayed Y-hang at the head of a superb free-hang into the main passage of the cave. The rebelay has a conveniently placed platform of jammed rocks to stand on. The shaft lands in the grandure of the main river passage, passing a short side passage part way down. Waterfalls shower in from high in the ceiling, and the thunder of the river echoes from below the boulders. For a Welsh cave, this is a very impressive introduction.

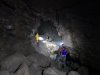

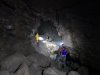

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Sol and Pete

The shaft lands in the grandure of the main river passage, passing a short side passage part way down. Waterfalls shower in from high in the ceiling, and the thunder of the river echoes from below the boulders. For a Welsh cave, this is a very impressive introduction.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Sol and Pete This sheep was not so lucky. And as for whose leather boot is on the rock behind the bones, your guess is as good as mine.

This sheep was not so lucky. And as for whose leather boot is on the rock behind the bones, your guess is as good as mine. A newtlet, only just metamorphosed from a tadpole, on the floor of the pitch, with a finger tip for scale. They appear to be palmate newts, and the surrounding peat bog is the perfect habitat for them, but they could be smooth instead (I did not examine their bellies to check for the identification, but the eyes suggest smooth, while the back pattern suggests palmate). There is plenty of good food here, and there is a thriving colony of them. It is not known whether they are breeding down here (there is plenty of opportunity) or just falling in from the surface, but there are a large number down here.

Modelling by Tarquin's finger and Mini

A newtlet, only just metamorphosed from a tadpole, on the floor of the pitch, with a finger tip for scale. They appear to be palmate newts, and the surrounding peat bog is the perfect habitat for them, but they could be smooth instead (I did not examine their bellies to check for the identification, but the eyes suggest smooth, while the back pattern suggests palmate). There is plenty of good food here, and there is a thriving colony of them. It is not known whether they are breeding down here (there is plenty of opportunity) or just falling in from the surface, but there are a large number down here.

Modelling by Tarquin's finger and Mini Juvenile, with the pattern now changed to a stripe.

Modelling by Punky

Juvenile, with the pattern now changed to a stripe.

Modelling by Punky Newt and common toad, both living here.

Modelling by Cadewyn and Larry

Newt and common toad, both living here.

Modelling by Cadewyn and Larry The newt is adult, and appears to be female, though this is out of season so it could be male. The cloacal bulge is normal for females of this species, while the size of the belly suggests there is no shortage of food.

Modelling by Cadewyn

The newt is adult, and appears to be female, though this is out of season so it could be male. The cloacal bulge is normal for females of this species, while the size of the belly suggests there is no shortage of food.

Modelling by Cadewyn The toad did not want to come out and play. Face firmly shoved into the rocks, if it can't see us, we don't exist.

Modelling by Larry

The toad did not want to come out and play. Face firmly shoved into the rocks, if it can't see us, we don't exist.

Modelling by Larry A quick foray into the upstream passage. The dry loop bypasses a drop down into the river.

Modelling by Pete

A quick foray into the upstream passage. The dry loop bypasses a drop down into the river.

Modelling by Pete Grotto in the dry loop.

Grotto in the dry loop. Curtain in the grotto; dry and quite lifeless.

Curtain in the grotto; dry and quite lifeless. Rejoining the river.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete

Rejoining the river.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete Downstream reaches the bottom of an impossible climb back up to the entrance chamber.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete

Downstream reaches the bottom of an impossible climb back up to the entrance chamber.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete Through a curtain of water upstream. The water charges through this passage effortlessly, while we have to pass between the chert shelves. The passage is much smaller than the downstream end, so this is clearly a much more recent development, and not the original source of the downstream passage's size.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete

Through a curtain of water upstream. The water charges through this passage effortlessly, while we have to pass between the chert shelves. The passage is much smaller than the downstream end, so this is clearly a much more recent development, and not the original source of the downstream passage's size.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete Upstream river passage.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Pete

Upstream river passage.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Pete The passage ends at a dramatic waterfall. This is seen in very high water here, and would not normally be quite so impressive. This can be climbed either directly, or via a narrow cleft, but the passage at the top is a low bedding which becomes too tight. Today was not the day to try it.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete

The passage ends at a dramatic waterfall. This is seen in very high water here, and would not normally be quite so impressive. This can be climbed either directly, or via a narrow cleft, but the passage at the top is a low bedding which becomes too tight. Today was not the day to try it.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete The downstream direction starts as an impressive river passage, with the combined streams adding some excitement. While it was possible to hear each other, the river was definitely very loud.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

The downstream direction starts as an impressive river passage, with the combined streams adding some excitement. While it was possible to hear each other, the river was definitely very loud.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Massive fallen slabs.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

Massive fallen slabs.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules This passage is far too grand to have been created by the upstream passage, so the entrance was clearly the more substantial sink while it was active.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

This passage is far too grand to have been created by the upstream passage, so the entrance was clearly the more substantial sink while it was active.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete The passage them chokes at The Wine Press, where the way on is down to the right, into an undercut containing the First Boulder Choke.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

The passage them chokes at The Wine Press, where the way on is down to the right, into an undercut containing the First Boulder Choke.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules In the middle of the choke, having reached the water. There is now a series of choices as to which of the many obvious ways on actually works, but it eventually ends up at a climb up through Second Boulder Choke (which is not even a ruckle) into a chamber.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules

In the middle of the choke, having reached the water. There is now a series of choices as to which of the many obvious ways on actually works, but it eventually ends up at a climb up through Second Boulder Choke (which is not even a ruckle) into a chamber.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules The climb reaches Straw Chamber, with its collection of rather small straws.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules

The climb reaches Straw Chamber, with its collection of rather small straws.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules Straw grill.

Straw grill. Top of Straw Chamber.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

Top of Straw Chamber.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Bottom of Straw Chamber, with its distinctive stalagmites, and a radon detector.

Bottom of Straw Chamber, with its distinctive stalagmites, and a radon detector. The passage behind the stalagmites contains some curtains, and ends at a very steep scramble back to the stream.

The passage behind the stalagmites contains some curtains, and ends at a very steep scramble back to the stream. Instead, a drop down into The Oxbow (yes, that's its name) provides an alternative.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

Instead, a drop down into The Oxbow (yes, that's its name) provides an alternative.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Straws in The Oxbow.

Straws in The Oxbow. Helictites in The Oxbow.

Helictites in The Oxbow. Helictites in The Oxbow.

Helictites in The Oxbow. Helictites in The Oxbow.

Helictites in The Oxbow. Helictites in The Oxbow.

Helictites in The Oxbow. Helictites in The Oxbow.

Helictites in The Oxbow. Helictites in The Oxbow.

Helictites in The Oxbow. Helictites in The Oxbow.

Helictites in The Oxbow. Straws in The Oxbow. A clamber down then reaches floor level.

Straws in The Oxbow. A clamber down then reaches floor level. The Oxbow rejoins the main route at a stunningly well decorated grotto. These are the most iconic set of straws and stalactites, with the distinctively coloured cluster.

Lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

The Oxbow rejoins the main route at a stunningly well decorated grotto. These are the most iconic set of straws and stalactites, with the distinctively coloured cluster.

Lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules In the grotto.

Lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

In the grotto.

Lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules In the grotto.

Lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

In the grotto.

Lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules In the grotto.

In the grotto. The most densely packed set of straws, filling a bedding.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules

The most densely packed set of straws, filling a bedding.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules At the next bend, a ramp of boulders on the left is the way into The Chapel, a passage that is not on the survey. This may have been an intentional move, to avoid sending too many people here, as it is highly decorated, and vulnerable.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

At the next bend, a ramp of boulders on the left is the way into The Chapel, a passage that is not on the survey. This may have been an intentional move, to avoid sending too many people here, as it is highly decorated, and vulnerable.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Curtain and straws at the junction.

Curtain and straws at the junction. A calcite ramp on the left is the way to The Chapel.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

A calcite ramp on the left is the way to The Chapel.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules The helictites start immediately.

The helictites start immediately. Helictites and straws.

Helictites and straws. Densely packed helictites.

Densely packed helictites. Helictites.

Helictites. Helictites.

Helictites. Arch of straws.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

Arch of straws.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Straws on the route to The Chapel.

Straws on the route to The Chapel. Curtain hidden among the helictites.

Curtain hidden among the helictites. Passage into The Chapel.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Jules

Passage into The Chapel.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Jules The Chapel is absolutely the highlight of the cave, and one of the best decorated grottos in the area. Straws and intricate helictites.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The Chapel is absolutely the highlight of the cave, and one of the best decorated grottos in the area. Straws and intricate helictites.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete Profusion of straws in The Chapel, with a shelf covered in helictites.

Profusion of straws in The Chapel, with a shelf covered in helictites. Straws.

Straws. Admiring the formations.

Modelling by Jules

Admiring the formations.

Modelling by Jules Some of the longest helictites in The Chapel, several of which twist around for 20 cm.

Modelling by the digits of Jules

Some of the longest helictites in The Chapel, several of which twist around for 20 cm.

Modelling by the digits of Jules The main set of the helictites.

The main set of the helictites. The helictite shelf.

The helictite shelf. Above the helictite shelf.

Above the helictite shelf. On the helictite shelf.

On the helictite shelf. The longest of the helictites sits in the ceiling above the shelf, about 30 cm long.

The longest of the helictites sits in the ceiling above the shelf, about 30 cm long. The other side of the grotto is also covered in helictites.

The other side of the grotto is also covered in helictites. Helicites on the opposite wall.

Helicites on the opposite wall. Helictites on the opposite wall.

Helictites on the opposite wall. Helictites on the opposite wall.

Helictites on the opposite wall. Stalactite below the shelf.

Stalactite below the shelf. Remains of a crystal pool on the floor.

Remains of a crystal pool on the floor. To the right at the junction is a boulder pile with more formations. Getting above here requires a scramble or a slither between the boulders.

To the right at the junction is a boulder pile with more formations. Getting above here requires a scramble or a slither between the boulders. Stalactites above the junction.

Stalactites above the junction. The climb reaches a beautifully decorated chamber, with a balcony overlooking the river.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The climb reaches a beautifully decorated chamber, with a balcony overlooking the river.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete Decomposing calcite in the chamber.

Decomposing calcite in the chamber. Clusters of stalatites and straws in the streamway.

Clusters of stalatites and straws in the streamway. Descending back to the river. We had apparently crossed a slab called The Table, but had not noticed.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

Descending back to the river. We had apparently crossed a slab called The Table, but had not noticed.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete Flowstone formations in the streamway.

Flowstone formations in the streamway. The streamway is well decorated, with distinct pods of stalatites and straws.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The streamway is well decorated, with distinct pods of stalatites and straws.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete Stal cluster.

Stal cluster. Another stal cluster.

Lighting by Tarquin and Pete

Another stal cluster.

Lighting by Tarquin and Pete Below the stal clusters.

Below the stal clusters. Straws covering the ceiling. This really is a well decorated passage.

Straws covering the ceiling. This really is a well decorated passage. Sabre Junction, named after the iconic Sabre formation; a curtain with a sceptre-like ornamentation at its end.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

Sabre Junction, named after the iconic Sabre formation; a curtain with a sceptre-like ornamentation at its end.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete The curtains at Sabre Junction are very grand, with waterfalls showering in. This is a really impressive place. On one side is an aven, with the passage at the top soon ending.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

The curtains at Sabre Junction are very grand, with waterfalls showering in. This is a really impressive place. On one side is an aven, with the passage at the top soon ending.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules The bizarre stalactite clusters continue.

The bizarre stalactite clusters continue. Beyond Sabre Junction, the river passage returns to its former style, with fewer formations.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

Beyond Sabre Junction, the river passage returns to its former style, with fewer formations.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete The flood scum was quite obvious, being quite some distance up above the current river level. It was very fresh, with the bubbles popping as we walked past. It had probably been washed into position by flood water the night before.

The flood scum was quite obvious, being quite some distance up above the current river level. It was very fresh, with the bubbles popping as we walked past. It had probably been washed into position by flood water the night before. The stal in the ceiling is covered in flecks of mud, suggesting that at some point this passage had seen some severe flooding, but this appears to be historical.

The stal in the ceiling is covered in flecks of mud, suggesting that at some point this passage had seen some severe flooding, but this appears to be historical. The narrow section before Third Boulder Choke. This is the only point we had been concerned about with the water levels, but this could clearly be passed in much more severe conditions.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules

The narrow section before Third Boulder Choke. This is the only point we had been concerned about with the water levels, but this could clearly be passed in much more severe conditions.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules Formations in the narrow section.

Formations in the narrow section. Dusty formations immediately before Third Boulder Choke, whose boulder slope can be seen in the background. Again, the choke is not a big obstacle, and is barely a ruckle.

Lighting by Tarquin and Jules

Dusty formations immediately before Third Boulder Choke, whose boulder slope can be seen in the background. Again, the choke is not a big obstacle, and is barely a ruckle.

Lighting by Tarquin and Jules Fracture in a huge stalagmite boss. The floor apparently dropped a bit.

Fracture in a huge stalagmite boss. The floor apparently dropped a bit. The Third Boulder Choke emerges in The Great Hall, the largest passage in the cave. Its size is clearly a product of the two passages joining here, but there is also a line a weakness, with several waterfalls joining at this point.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The Third Boulder Choke emerges in The Great Hall, the largest passage in the cave. Its size is clearly a product of the two passages joining here, but there is also a line a weakness, with several waterfalls joining at this point.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete Curtain in The Great Hall.

Curtain in The Great Hall. On the right is The Graveyard, the most significant side passage in the cave.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

On the right is The Graveyard, the most significant side passage in the cave.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Drip formations in The Graveyard.

Drip formations in The Graveyard. Formations in The Graveyard.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

Formations in The Graveyard.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Flowstone formation.

Flowstone formation. Crystal pools in the flowstone.

Crystal pools in the flowstone. Translucent curtain in The Graveyard.

Translucent curtain in The Graveyard. The Graveyard then ends abruptly. Although there are ways beyond here, the grandure of The Graveyard is never regained.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The Graveyard then ends abruptly. Although there are ways beyond here, the grandure of The Graveyard is never regained.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete A wet crawl under the wall gains a smaller passage.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete

A wet crawl under the wall gains a smaller passage.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete In one direction is a climb up into The Organ Loft (shown as The Organ on some surveys). This proved to need mountain goat abilities, and a rope proved very useful.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

In one direction is a climb up into The Organ Loft (shown as The Organ on some surveys). This proved to need mountain goat abilities, and a rope proved very useful.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Curtain below the climb.

Curtain below the climb. Pipes in The Organ Loft.

Pipes in The Organ Loft. The Organ Loft is a particularly well decorated little chamber, with abundant crystal pools. The way on through The Graveyard, if one is ever found, is likely to pass beneath the floor, heading to the left here. The fog is from the river rather than us; the humidity was really high in here.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

The Organ Loft is a particularly well decorated little chamber, with abundant crystal pools. The way on through The Graveyard, if one is ever found, is likely to pass beneath the floor, heading to the left here. The fog is from the river rather than us; the humidity was really high in here.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Flowstone blockage at the end of The Organ Loft.

Flowstone blockage at the end of The Organ Loft. Small crystal pool with a strongly arched meniscus in The Organ Loft.

Small crystal pool with a strongly arched meniscus in The Organ Loft. Larger crystal pool. The meniscus can be seen again by the lensing patterns around the flowstone's shadow.

Larger crystal pool. The meniscus can be seen again by the lensing patterns around the flowstone's shadow. Short side passage ending at a curtain formation.

Lighting by Tarquin and Pete

Short side passage ending at a curtain formation.

Lighting by Tarquin and Pete Stal in an alcove.

Stal in an alcove. Heavily fossilised rock layer within the boulders in The Organ Loft.

Heavily fossilised rock layer within the boulders in The Organ Loft. In the opposite direction from The Organ Loft is a climb up into The Vestry. This one is badly overhanging without sufficient holds, so the best approach is to climb up into a small hole where the water flows out, and crawl through with the stream. Refreshing.

Modelling by Pete

In the opposite direction from The Organ Loft is a climb up into The Vestry. This one is badly overhanging without sufficient holds, so the best approach is to climb up into a small hole where the water flows out, and crawl through with the stream. Refreshing.

Modelling by Pete The Vestry has very few formations, but a few inlets. The passage up on the right is by far the most promising. On a previous visit here, I had climbed up to that passage, and had a hold break off, causing me to fall all the way to the floor from ceiling height, landing on my back. Fortunately without any injury. I still do not know if that passage actually goes anywhere, as I did not want to risk a repeat of that incident.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

The Vestry has very few formations, but a few inlets. The passage up on the right is by far the most promising. On a previous visit here, I had climbed up to that passage, and had a hold break off, causing me to fall all the way to the floor from ceiling height, landing on my back. Fortunately without any injury. I still do not know if that passage actually goes anywhere, as I did not want to risk a repeat of that incident.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules An alternative way into the passage appears to be a flat out crawl into a water chute which descends from that passage. None of us wanted to subject ourselves to trying that approach.

An alternative way into the passage appears to be a flat out crawl into a water chute which descends from that passage. None of us wanted to subject ourselves to trying that approach. Returning to the river passage, the grandure of The Great Hall continues for some distance.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

Returning to the river passage, the grandure of The Great Hall continues for some distance.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete The passage then shrinks back to its former size, and the mud banks start. There is no sign of this part flooding, but it certainly has at some point.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The passage then shrinks back to its former size, and the mud banks start. There is no sign of this part flooding, but it certainly has at some point.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete The Fire Hydrant, a forceful inlet jetting into an undercut. The river was so loud at this point that we did not notice it on the way in.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete

The Fire Hydrant, a forceful inlet jetting into an undercut. The river was so loud at this point that we did not notice it on the way in.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete The river then becomes dominated by the mudbanks, which are used to bypass the occasional deeper pools. The stal flows on one wall are covered in mud and black staining, showing that this area has seen some extensive flooding.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The river then becomes dominated by the mudbanks, which are used to bypass the occasional deeper pools. The stal flows on one wall are covered in mud and black staining, showing that this area has seen some extensive flooding.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete The most substantial side passage here is Dead End, a wide passage at ceiling level that might have been the former downstream route, which would explain why the rest of the cave is the size that it is.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

The most substantial side passage here is Dead End, a wide passage at ceiling level that might have been the former downstream route, which would explain why the rest of the cave is the size that it is.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules The start of Dead End is marked by a large pile of mud-stained stal, which has been broken and twisted by subsidence.

The start of Dead End is marked by a large pile of mud-stained stal, which has been broken and twisted by subsidence. Layers of the stal, which have been redissolved.

Layers of the stal, which have been redissolved. There are several piles of small pebbles throughout the cave, such as these in Dead End, which really look like cryostal. But they would appear to be just quartz pebbles from the millstone grit caprock.

There are several piles of small pebbles throughout the cave, such as these in Dead End, which really look like cryostal. But they would appear to be just quartz pebbles from the millstone grit caprock. The Dead End Dig tools. This was clearly a major effort. It takes some dedication to get a wheelbarrow all this way in.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The Dead End Dig tools. This was clearly a major effort. It takes some dedication to get a wheelbarrow all this way in.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete Elaborate patterns in the mould from an old plank.

Lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

Elaborate patterns in the mould from an old plank.

Lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Crazy mould patterns.

Crazy mould patterns. Invasive stream inlet in Dead End. This was not responsible for making the passage.

Invasive stream inlet in Dead End. This was not responsible for making the passage. Dead End ends at two digs. The right-hand dig quickly gets very wet, which is presumably why the syphoning hose was there.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

Dead End ends at two digs. The right-hand dig quickly gets very wet, which is presumably why the syphoning hose was there.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules The left dig is longer, becoming flat-out for a long distance. None of us wanted to push through it.

The left dig is longer, becoming flat-out for a long distance. None of us wanted to push through it. Stal pouring from a hole in the ceiling. The mud stains are no longer just a historical remnant. This area floods. Severely.

Stal pouring from a hole in the ceiling. The mud stains are no longer just a historical remnant. This area floods. Severely. Worm casts in the mud banks. No worms were seen, but they definitely live here.

Worm casts in the mud banks. No worms were seen, but they definitely live here. The passage then becomes much lower, presumably a former sump. This part can probably flood to the ceiling.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete

The passage then becomes much lower, presumably a former sump. This part can probably flood to the ceiling.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete Substantial web hanging from the ceiling. The tiny threads are made by fungus gnats (small flies), but these big threads look much more impressive. We were not able to tell immediately if they were made by animals or fungus. This would be a very long way in for a large spider to survive here.

Substantial web hanging from the ceiling. The tiny threads are made by fungus gnats (small flies), but these big threads look much more impressive. We were not able to tell immediately if they were made by animals or fungus. This would be a very long way in for a large spider to survive here. An even more impressive web.

An even more impressive web. The passage narrows as the route passes through a cleft in the roof. The stal boss has a rope hanging down it, which is the way up into Dilly's Despair. This is a short aven series which parallels the streamway, ending in a dig.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete

The passage narrows as the route passes through a cleft in the roof. The stal boss has a rope hanging down it, which is the way up into Dilly's Despair. This is a short aven series which parallels the streamway, ending in a dig.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete The final section of cave really brings home just how much it can flood. The wall at the top of the mud slope is covered in flood scum. The current river level can be seen down in the distance. It appears to back up from the end of the cave, rather than a heavy pulse from above. That flood scum is fresh, from the night before our visit. On returning to this point, the sound of the river had completely changed, now with a deeper rumble, and this definitely made me feel quite uneasy. However, the flooding appears to have ended before our visit, and the sound change was likely caused by a reduction in flow rather than an increase.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The final section of cave really brings home just how much it can flood. The wall at the top of the mud slope is covered in flood scum. The current river level can be seen down in the distance. It appears to back up from the end of the cave, rather than a heavy pulse from above. That flood scum is fresh, from the night before our visit. On returning to this point, the sound of the river had completely changed, now with a deeper rumble, and this definitely made me feel quite uneasy. However, the flooding appears to have ended before our visit, and the sound change was likely caused by a reduction in flow rather than an increase.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete The passage narrows to a rift (where did all the big stuff go?), and the walls were absolutely covered in flood scum, showing several ponding levels. The ceiling, 6 metres above, was covered in fresh foam, so this entire passage had been full of water just a few hours earlier.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The passage narrows to a rift (where did all the big stuff go?), and the walls were absolutely covered in flood scum, showing several ponding levels. The ceiling, 6 metres above, was covered in fresh foam, so this entire passage had been full of water just a few hours earlier.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete Fresh flood scum.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules

Fresh flood scum.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules Tall rift near the end of the cave, still covered in fresh scum. This was impressive, and also a little intimidating. If only there was a way to make yourself feel better about it all.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

Tall rift near the end of the cave, still covered in fresh scum. This was impressive, and also a little intimidating. If only there was a way to make yourself feel better about it all.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete Problem solved. There is no visible scum.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Pete

Problem solved. There is no visible scum.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Pete The passage then gets lower, with the river charging through the narrow sections.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The passage then gets lower, with the river charging through the narrow sections.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete The water then gets deeper, and the ceiling eventually lowers to meet it. The sump has never been passed, but dye tracing has connected it to resurgences in the Nedd Fechan, a huge distance away. There is a lot of cave waiting to be found.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

The water then gets deeper, and the ceiling eventually lowers to meet it. The sump has never been passed, but dye tracing has connected it to resurgences in the Nedd Fechan, a huge distance away. There is a lot of cave waiting to be found.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules During our exit, we met a university team who were also exiting from Second Boulder Choke, as one of their team needed to abort the trip. We adopted their team member, allowing the rest to complete their trip. She had never done SRT before, and was on her first ever caving trip, down a shaft, with no SRT training. We gave her a crash course, and guided her out with a tandem prussic (using their separate rope), and a supervised series of manoeuvres at the top. All things considered, she did admirably, bravo Mia! Just so you understand, this is most definitely not the right way to take a novice caving. SRT is a technical skill that needs to be taught correctly in a much more controlled environment, where a person can be properly observed and coached. They need to be proficient before they use these techniques in a cave, as they rely on their technique and rehersed routines to protect their life. If you are a university group that thinks this is a good way to take novices caving, you should seriously reconsider your responsibilities for someone else's life. SRT is great, and it opens up a world of more advanced caving, but you should practice it safely, several times, before using it in a cave.

Modelling by Mia Sannapureddy and Jules, lighting by Mia, Jules and Sol

During our exit, we met a university team who were also exiting from Second Boulder Choke, as one of their team needed to abort the trip. We adopted their team member, allowing the rest to complete their trip. She had never done SRT before, and was on her first ever caving trip, down a shaft, with no SRT training. We gave her a crash course, and guided her out with a tandem prussic (using their separate rope), and a supervised series of manoeuvres at the top. All things considered, she did admirably, bravo Mia! Just so you understand, this is most definitely not the right way to take a novice caving. SRT is a technical skill that needs to be taught correctly in a much more controlled environment, where a person can be properly observed and coached. They need to be proficient before they use these techniques in a cave, as they rely on their technique and rehersed routines to protect their life. If you are a university group that thinks this is a good way to take novices caving, you should seriously reconsider your responsibilities for someone else's life. SRT is great, and it opens up a world of more advanced caving, but you should practice it safely, several times, before using it in a cave.

Modelling by Mia Sannapureddy and Jules, lighting by Mia, Jules and Sol Returning past Chas's Dig.

Modelling by Pete and Jules

Returning past Chas's Dig.

Modelling by Pete and Jules This is interestingly positioned, as it sits upstream of Pwll Byfre, and may have potential to find an upstream feeder to the system, or even cross over to Pant Mawr, since it sits near the watershed.

This is interestingly positioned, as it sits upstream of Pwll Byfre, and may have potential to find an upstream feeder to the system, or even cross over to Pant Mawr, since it sits near the watershed. Sunset over Cribarth, a really fitting end to a great trip. The distant hills are the Mynydd y Betws range, topping out at Penlle'r Castell (371 metres).

Modelling by Pete

Sunset over Cribarth, a really fitting end to a great trip. The distant hills are the Mynydd y Betws range, topping out at Penlle'r Castell (371 metres).

Modelling by Pete The entrance to Hot Air Mine, a cave that nearly connects to Ogof Ffynnon Ddu III.

The entrance to Hot Air Mine, a cave that nearly connects to Ogof Ffynnon Ddu III. Exposed limestone pavement in the Ogof Ffynnon Ddu nature reserve.

Modelling by Jules and Mia

Exposed limestone pavement in the Ogof Ffynnon Ddu nature reserve.

Modelling by Jules and Mia

View over the upper Tawe valley. Carreg Lwyd crags, Hirfynydd (481 metres), Mynydd Marchywel (418 metres), Cribarth (428 metres), Carreg Goch (558 metres), Garreg Las (635 metres), Fan Hir (761 metres), Cefn Cul (562 metres) and Fan Gyhirych (725 metres).

Modelling by Pete

View over the upper Tawe valley. Carreg Lwyd crags, Hirfynydd (481 metres), Mynydd Marchywel (418 metres), Cribarth (428 metres), Carreg Goch (558 metres), Garreg Las (635 metres), Fan Hir (761 metres), Cefn Cul (562 metres) and Fan Gyhirych (725 metres).

Modelling by Pete Walking into the basin of the Byrfre Fechan. The Nant Byfre flows off to the left, while the Byfre Fechan sinks into the basin. On the left are the flanks of Fan Gyhirych, but the top is hidden some distance away. On the right are the Carreg Cadno outcrops (538 metres).

Modelling by Pete and Jules

Walking into the basin of the Byrfre Fechan. The Nant Byfre flows off to the left, while the Byfre Fechan sinks into the basin. On the left are the flanks of Fan Gyhirych, but the top is hidden some distance away. On the right are the Carreg Cadno outcrops (538 metres).

Modelling by Pete and Jules Striding past the deeply incised sinks at Pwll Byfre. The location of the sink has migrated in the past, and so far all of them have resisted digging.

Modelling by Pete and Jules

Striding past the deeply incised sinks at Pwll Byfre. The location of the sink has migrated in the past, and so far all of them have resisted digging.

Modelling by Pete and Jules The main Pwll Byfre, with a swollen river forming a lake in the main sink. This is the upper end of the Ogof Ffynnon Ddu system, with the known cave ending some distance away to the right.

The main Pwll Byfre, with a swollen river forming a lake in the main sink. This is the upper end of the Ogof Ffynnon Ddu system, with the known cave ending some distance away to the right. Crossing the watershed into Pant Mawr; the big hollow. The cave's stream drains the left edge of the forest, and can produce a surprising amount of water. The entrance can be seen as a dark spot just below the right edge of the trees. Fan Fraith (668 metres), Fan Nedd (663 metres), Fan Llia (632 metres), a distant Cefn yr Ystrad (617 metres) and Carreg Cadno.

Modelling by Tarquin's shadow, Jules and Pete

Crossing the watershed into Pant Mawr; the big hollow. The cave's stream drains the left edge of the forest, and can produce a surprising amount of water. The entrance can be seen as a dark spot just below the right edge of the trees. Fan Fraith (668 metres), Fan Nedd (663 metres), Fan Llia (632 metres), a distant Cefn yr Ystrad (617 metres) and Carreg Cadno.

Modelling by Tarquin's shadow, Jules and Pete The shakehole entrance of Pant Mawr Pot. Despite the name, it is not really a pothole, it is a substantial cave with a single pitch entrance. It is academic as to what constitutes a pothole rather than a cave, but Ogof Draenen has perhaps 100 pitches, but would never be considered a pothole. A typical pothole would need to either consist almost entirely of a vertical system, or have multiple pitches on its primary routes. This is neither. Nevertheless, it starts out as a pitch, and a backup handline is required right from the start to descend into the shakehole.

Modelling by Tarquin's shadow, Pete and Jules

The shakehole entrance of Pant Mawr Pot. Despite the name, it is not really a pothole, it is a substantial cave with a single pitch entrance. It is academic as to what constitutes a pothole rather than a cave, but Ogof Draenen has perhaps 100 pitches, but would never be considered a pothole. A typical pothole would need to either consist almost entirely of a vertical system, or have multiple pitches on its primary routes. This is neither. Nevertheless, it starts out as a pitch, and a backup handline is required right from the start to descend into the shakehole.

Modelling by Tarquin's shadow, Pete and Jules The pitch head begins with a backup, Y-hang, then down to a rebelayed Y-hang at the head of a superb free-hang into the main passage of the cave. The rebelay has a conveniently placed platform of jammed rocks to stand on.

The pitch head begins with a backup, Y-hang, then down to a rebelayed Y-hang at the head of a superb free-hang into the main passage of the cave. The rebelay has a conveniently placed platform of jammed rocks to stand on. The shaft lands in the grandure of the main river passage, passing a short side passage part way down. Waterfalls shower in from high in the ceiling, and the thunder of the river echoes from below the boulders. For a Welsh cave, this is a very impressive introduction.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Sol and Pete

The shaft lands in the grandure of the main river passage, passing a short side passage part way down. Waterfalls shower in from high in the ceiling, and the thunder of the river echoes from below the boulders. For a Welsh cave, this is a very impressive introduction.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Sol and Pete This sheep was not so lucky. And as for whose leather boot is on the rock behind the bones, your guess is as good as mine.

This sheep was not so lucky. And as for whose leather boot is on the rock behind the bones, your guess is as good as mine. A newtlet, only just metamorphosed from a tadpole, on the floor of the pitch, with a finger tip for scale. They appear to be palmate newts, and the surrounding peat bog is the perfect habitat for them, but they could be smooth instead (I did not examine their bellies to check for the identification, but the eyes suggest smooth, while the back pattern suggests palmate). There is plenty of good food here, and there is a thriving colony of them. It is not known whether they are breeding down here (there is plenty of opportunity) or just falling in from the surface, but there are a large number down here.

Modelling by Tarquin's finger and Mini

A newtlet, only just metamorphosed from a tadpole, on the floor of the pitch, with a finger tip for scale. They appear to be palmate newts, and the surrounding peat bog is the perfect habitat for them, but they could be smooth instead (I did not examine their bellies to check for the identification, but the eyes suggest smooth, while the back pattern suggests palmate). There is plenty of good food here, and there is a thriving colony of them. It is not known whether they are breeding down here (there is plenty of opportunity) or just falling in from the surface, but there are a large number down here.

Modelling by Tarquin's finger and Mini Juvenile, with the pattern now changed to a stripe.

Modelling by Punky

Juvenile, with the pattern now changed to a stripe.

Modelling by Punky Newt and common toad, both living here.

Modelling by Cadewyn and Larry

Newt and common toad, both living here.

Modelling by Cadewyn and Larry The newt is adult, and appears to be female, though this is out of season so it could be male. The cloacal bulge is normal for females of this species, while the size of the belly suggests there is no shortage of food.

Modelling by Cadewyn

The newt is adult, and appears to be female, though this is out of season so it could be male. The cloacal bulge is normal for females of this species, while the size of the belly suggests there is no shortage of food.

Modelling by Cadewyn The toad did not want to come out and play. Face firmly shoved into the rocks, if it can't see us, we don't exist.

Modelling by Larry

The toad did not want to come out and play. Face firmly shoved into the rocks, if it can't see us, we don't exist.

Modelling by Larry A quick foray into the upstream passage. The dry loop bypasses a drop down into the river.

Modelling by Pete

A quick foray into the upstream passage. The dry loop bypasses a drop down into the river.

Modelling by Pete Grotto in the dry loop.

Grotto in the dry loop. Curtain in the grotto; dry and quite lifeless.

Curtain in the grotto; dry and quite lifeless. Rejoining the river.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete

Rejoining the river.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete Downstream reaches the bottom of an impossible climb back up to the entrance chamber.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete

Downstream reaches the bottom of an impossible climb back up to the entrance chamber.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete Through a curtain of water upstream. The water charges through this passage effortlessly, while we have to pass between the chert shelves. The passage is much smaller than the downstream end, so this is clearly a much more recent development, and not the original source of the downstream passage's size.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete

Through a curtain of water upstream. The water charges through this passage effortlessly, while we have to pass between the chert shelves. The passage is much smaller than the downstream end, so this is clearly a much more recent development, and not the original source of the downstream passage's size.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete Upstream river passage.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Pete

Upstream river passage.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Pete The passage ends at a dramatic waterfall. This is seen in very high water here, and would not normally be quite so impressive. This can be climbed either directly, or via a narrow cleft, but the passage at the top is a low bedding which becomes too tight. Today was not the day to try it.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete

The passage ends at a dramatic waterfall. This is seen in very high water here, and would not normally be quite so impressive. This can be climbed either directly, or via a narrow cleft, but the passage at the top is a low bedding which becomes too tight. Today was not the day to try it.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete The downstream direction starts as an impressive river passage, with the combined streams adding some excitement. While it was possible to hear each other, the river was definitely very loud.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

The downstream direction starts as an impressive river passage, with the combined streams adding some excitement. While it was possible to hear each other, the river was definitely very loud.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Massive fallen slabs.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

Massive fallen slabs.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules This passage is far too grand to have been created by the upstream passage, so the entrance was clearly the more substantial sink while it was active.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

This passage is far too grand to have been created by the upstream passage, so the entrance was clearly the more substantial sink while it was active.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete The passage them chokes at The Wine Press, where the way on is down to the right, into an undercut containing the First Boulder Choke.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

The passage them chokes at The Wine Press, where the way on is down to the right, into an undercut containing the First Boulder Choke.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules In the middle of the choke, having reached the water. There is now a series of choices as to which of the many obvious ways on actually works, but it eventually ends up at a climb up through Second Boulder Choke (which is not even a ruckle) into a chamber.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules

In the middle of the choke, having reached the water. There is now a series of choices as to which of the many obvious ways on actually works, but it eventually ends up at a climb up through Second Boulder Choke (which is not even a ruckle) into a chamber.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules The climb reaches Straw Chamber, with its collection of rather small straws.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules

The climb reaches Straw Chamber, with its collection of rather small straws.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules Straw grill.

Straw grill. Top of Straw Chamber.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

Top of Straw Chamber.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Bottom of Straw Chamber, with its distinctive stalagmites, and a radon detector.

Bottom of Straw Chamber, with its distinctive stalagmites, and a radon detector. The passage behind the stalagmites contains some curtains, and ends at a very steep scramble back to the stream.

The passage behind the stalagmites contains some curtains, and ends at a very steep scramble back to the stream. Instead, a drop down into The Oxbow (yes, that's its name) provides an alternative.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

Instead, a drop down into The Oxbow (yes, that's its name) provides an alternative.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Straws in The Oxbow.

Straws in The Oxbow. Helictites in The Oxbow.

Helictites in The Oxbow. Helictites in The Oxbow.

Helictites in The Oxbow. Helictites in The Oxbow.

Helictites in The Oxbow. Helictites in The Oxbow.

Helictites in The Oxbow. Helictites in The Oxbow.

Helictites in The Oxbow. Helictites in The Oxbow.

Helictites in The Oxbow. Helictites in The Oxbow.

Helictites in The Oxbow. Straws in The Oxbow. A clamber down then reaches floor level.

Straws in The Oxbow. A clamber down then reaches floor level. The Oxbow rejoins the main route at a stunningly well decorated grotto. These are the most iconic set of straws and stalactites, with the distinctively coloured cluster.

Lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

The Oxbow rejoins the main route at a stunningly well decorated grotto. These are the most iconic set of straws and stalactites, with the distinctively coloured cluster.

Lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules In the grotto.

Lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

In the grotto.

Lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules In the grotto.

Lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

In the grotto.

Lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules In the grotto.

In the grotto. The most densely packed set of straws, filling a bedding.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules

The most densely packed set of straws, filling a bedding.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules At the next bend, a ramp of boulders on the left is the way into The Chapel, a passage that is not on the survey. This may have been an intentional move, to avoid sending too many people here, as it is highly decorated, and vulnerable.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

At the next bend, a ramp of boulders on the left is the way into The Chapel, a passage that is not on the survey. This may have been an intentional move, to avoid sending too many people here, as it is highly decorated, and vulnerable.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Curtain and straws at the junction.

Curtain and straws at the junction. A calcite ramp on the left is the way to The Chapel.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

A calcite ramp on the left is the way to The Chapel.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules The helictites start immediately.

The helictites start immediately. Helictites and straws.

Helictites and straws. Densely packed helictites.

Densely packed helictites. Helictites.

Helictites. Helictites.

Helictites. Arch of straws.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

Arch of straws.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Straws on the route to The Chapel.

Straws on the route to The Chapel. Curtain hidden among the helictites.

Curtain hidden among the helictites. Passage into The Chapel.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Jules

Passage into The Chapel.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Jules The Chapel is absolutely the highlight of the cave, and one of the best decorated grottos in the area. Straws and intricate helictites.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The Chapel is absolutely the highlight of the cave, and one of the best decorated grottos in the area. Straws and intricate helictites.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete Profusion of straws in The Chapel, with a shelf covered in helictites.

Profusion of straws in The Chapel, with a shelf covered in helictites. Straws.

Straws. Admiring the formations.

Modelling by Jules

Admiring the formations.

Modelling by Jules Some of the longest helictites in The Chapel, several of which twist around for 20 cm.

Modelling by the digits of Jules

Some of the longest helictites in The Chapel, several of which twist around for 20 cm.

Modelling by the digits of Jules The main set of the helictites.

The main set of the helictites. The helictite shelf.

The helictite shelf. Above the helictite shelf.

Above the helictite shelf. On the helictite shelf.

On the helictite shelf. The longest of the helictites sits in the ceiling above the shelf, about 30 cm long.

The longest of the helictites sits in the ceiling above the shelf, about 30 cm long. The other side of the grotto is also covered in helictites.

The other side of the grotto is also covered in helictites. Helicites on the opposite wall.

Helicites on the opposite wall. Helictites on the opposite wall.

Helictites on the opposite wall. Helictites on the opposite wall.

Helictites on the opposite wall. Stalactite below the shelf.

Stalactite below the shelf. Remains of a crystal pool on the floor.

Remains of a crystal pool on the floor. To the right at the junction is a boulder pile with more formations. Getting above here requires a scramble or a slither between the boulders.

To the right at the junction is a boulder pile with more formations. Getting above here requires a scramble or a slither between the boulders. Stalactites above the junction.

Stalactites above the junction. The climb reaches a beautifully decorated chamber, with a balcony overlooking the river.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The climb reaches a beautifully decorated chamber, with a balcony overlooking the river.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete Decomposing calcite in the chamber.

Decomposing calcite in the chamber. Clusters of stalatites and straws in the streamway.

Clusters of stalatites and straws in the streamway. Descending back to the river. We had apparently crossed a slab called The Table, but had not noticed.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

Descending back to the river. We had apparently crossed a slab called The Table, but had not noticed.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete Flowstone formations in the streamway.

Flowstone formations in the streamway. The streamway is well decorated, with distinct pods of stalatites and straws.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The streamway is well decorated, with distinct pods of stalatites and straws.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete Stal cluster.

Stal cluster. Another stal cluster.

Lighting by Tarquin and Pete

Another stal cluster.

Lighting by Tarquin and Pete Below the stal clusters.

Below the stal clusters. Straws covering the ceiling. This really is a well decorated passage.

Straws covering the ceiling. This really is a well decorated passage. Sabre Junction, named after the iconic Sabre formation; a curtain with a sceptre-like ornamentation at its end.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

Sabre Junction, named after the iconic Sabre formation; a curtain with a sceptre-like ornamentation at its end.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete The curtains at Sabre Junction are very grand, with waterfalls showering in. This is a really impressive place. On one side is an aven, with the passage at the top soon ending.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

The curtains at Sabre Junction are very grand, with waterfalls showering in. This is a really impressive place. On one side is an aven, with the passage at the top soon ending.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules The bizarre stalactite clusters continue.

The bizarre stalactite clusters continue. Beyond Sabre Junction, the river passage returns to its former style, with fewer formations.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

Beyond Sabre Junction, the river passage returns to its former style, with fewer formations.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete The flood scum was quite obvious, being quite some distance up above the current river level. It was very fresh, with the bubbles popping as we walked past. It had probably been washed into position by flood water the night before.

The flood scum was quite obvious, being quite some distance up above the current river level. It was very fresh, with the bubbles popping as we walked past. It had probably been washed into position by flood water the night before. The stal in the ceiling is covered in flecks of mud, suggesting that at some point this passage had seen some severe flooding, but this appears to be historical.

The stal in the ceiling is covered in flecks of mud, suggesting that at some point this passage had seen some severe flooding, but this appears to be historical. The narrow section before Third Boulder Choke. This is the only point we had been concerned about with the water levels, but this could clearly be passed in much more severe conditions.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules

The narrow section before Third Boulder Choke. This is the only point we had been concerned about with the water levels, but this could clearly be passed in much more severe conditions.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin and Jules Formations in the narrow section.

Formations in the narrow section. Dusty formations immediately before Third Boulder Choke, whose boulder slope can be seen in the background. Again, the choke is not a big obstacle, and is barely a ruckle.

Lighting by Tarquin and Jules

Dusty formations immediately before Third Boulder Choke, whose boulder slope can be seen in the background. Again, the choke is not a big obstacle, and is barely a ruckle.

Lighting by Tarquin and Jules Fracture in a huge stalagmite boss. The floor apparently dropped a bit.

Fracture in a huge stalagmite boss. The floor apparently dropped a bit. The Third Boulder Choke emerges in The Great Hall, the largest passage in the cave. Its size is clearly a product of the two passages joining here, but there is also a line a weakness, with several waterfalls joining at this point.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The Third Boulder Choke emerges in The Great Hall, the largest passage in the cave. Its size is clearly a product of the two passages joining here, but there is also a line a weakness, with several waterfalls joining at this point.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete Curtain in The Great Hall.

Curtain in The Great Hall. On the right is The Graveyard, the most significant side passage in the cave.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

On the right is The Graveyard, the most significant side passage in the cave.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Drip formations in The Graveyard.

Drip formations in The Graveyard. Formations in The Graveyard.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

Formations in The Graveyard.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Flowstone formation.

Flowstone formation. Crystal pools in the flowstone.

Crystal pools in the flowstone. Translucent curtain in The Graveyard.

Translucent curtain in The Graveyard. The Graveyard then ends abruptly. Although there are ways beyond here, the grandure of The Graveyard is never regained.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The Graveyard then ends abruptly. Although there are ways beyond here, the grandure of The Graveyard is never regained.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete A wet crawl under the wall gains a smaller passage.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete

A wet crawl under the wall gains a smaller passage.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete In one direction is a climb up into The Organ Loft (shown as The Organ on some surveys). This proved to need mountain goat abilities, and a rope proved very useful.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

In one direction is a climb up into The Organ Loft (shown as The Organ on some surveys). This proved to need mountain goat abilities, and a rope proved very useful.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Curtain below the climb.

Curtain below the climb. Pipes in The Organ Loft.

Pipes in The Organ Loft. The Organ Loft is a particularly well decorated little chamber, with abundant crystal pools. The way on through The Graveyard, if one is ever found, is likely to pass beneath the floor, heading to the left here. The fog is from the river rather than us; the humidity was really high in here.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

The Organ Loft is a particularly well decorated little chamber, with abundant crystal pools. The way on through The Graveyard, if one is ever found, is likely to pass beneath the floor, heading to the left here. The fog is from the river rather than us; the humidity was really high in here.

Modelling by Pete and Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Flowstone blockage at the end of The Organ Loft.

Flowstone blockage at the end of The Organ Loft. Small crystal pool with a strongly arched meniscus in The Organ Loft.

Small crystal pool with a strongly arched meniscus in The Organ Loft. Larger crystal pool. The meniscus can be seen again by the lensing patterns around the flowstone's shadow.

Larger crystal pool. The meniscus can be seen again by the lensing patterns around the flowstone's shadow. Short side passage ending at a curtain formation.

Lighting by Tarquin and Pete

Short side passage ending at a curtain formation.

Lighting by Tarquin and Pete Stal in an alcove.

Stal in an alcove. Heavily fossilised rock layer within the boulders in The Organ Loft.

Heavily fossilised rock layer within the boulders in The Organ Loft. In the opposite direction from The Organ Loft is a climb up into The Vestry. This one is badly overhanging without sufficient holds, so the best approach is to climb up into a small hole where the water flows out, and crawl through with the stream. Refreshing.

Modelling by Pete

In the opposite direction from The Organ Loft is a climb up into The Vestry. This one is badly overhanging without sufficient holds, so the best approach is to climb up into a small hole where the water flows out, and crawl through with the stream. Refreshing.

Modelling by Pete The Vestry has very few formations, but a few inlets. The passage up on the right is by far the most promising. On a previous visit here, I had climbed up to that passage, and had a hold break off, causing me to fall all the way to the floor from ceiling height, landing on my back. Fortunately without any injury. I still do not know if that passage actually goes anywhere, as I did not want to risk a repeat of that incident.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

The Vestry has very few formations, but a few inlets. The passage up on the right is by far the most promising. On a previous visit here, I had climbed up to that passage, and had a hold break off, causing me to fall all the way to the floor from ceiling height, landing on my back. Fortunately without any injury. I still do not know if that passage actually goes anywhere, as I did not want to risk a repeat of that incident.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules An alternative way into the passage appears to be a flat out crawl into a water chute which descends from that passage. None of us wanted to subject ourselves to trying that approach.

An alternative way into the passage appears to be a flat out crawl into a water chute which descends from that passage. None of us wanted to subject ourselves to trying that approach. Returning to the river passage, the grandure of The Great Hall continues for some distance.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

Returning to the river passage, the grandure of The Great Hall continues for some distance.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete The passage then shrinks back to its former size, and the mud banks start. There is no sign of this part flooding, but it certainly has at some point.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The passage then shrinks back to its former size, and the mud banks start. There is no sign of this part flooding, but it certainly has at some point.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete The Fire Hydrant, a forceful inlet jetting into an undercut. The river was so loud at this point that we did not notice it on the way in.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete

The Fire Hydrant, a forceful inlet jetting into an undercut. The river was so loud at this point that we did not notice it on the way in.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete The river then becomes dominated by the mudbanks, which are used to bypass the occasional deeper pools. The stal flows on one wall are covered in mud and black staining, showing that this area has seen some extensive flooding.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The river then becomes dominated by the mudbanks, which are used to bypass the occasional deeper pools. The stal flows on one wall are covered in mud and black staining, showing that this area has seen some extensive flooding.

Modelling by Jules and Pete, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete The most substantial side passage here is Dead End, a wide passage at ceiling level that might have been the former downstream route, which would explain why the rest of the cave is the size that it is.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

The most substantial side passage here is Dead End, a wide passage at ceiling level that might have been the former downstream route, which would explain why the rest of the cave is the size that it is.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules The start of Dead End is marked by a large pile of mud-stained stal, which has been broken and twisted by subsidence.

The start of Dead End is marked by a large pile of mud-stained stal, which has been broken and twisted by subsidence. Layers of the stal, which have been redissolved.

Layers of the stal, which have been redissolved. There are several piles of small pebbles throughout the cave, such as these in Dead End, which really look like cryostal. But they would appear to be just quartz pebbles from the millstone grit caprock.

There are several piles of small pebbles throughout the cave, such as these in Dead End, which really look like cryostal. But they would appear to be just quartz pebbles from the millstone grit caprock. The Dead End Dig tools. This was clearly a major effort. It takes some dedication to get a wheelbarrow all this way in.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete

The Dead End Dig tools. This was clearly a major effort. It takes some dedication to get a wheelbarrow all this way in.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Jules and Pete Elaborate patterns in the mould from an old plank.

Lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

Elaborate patterns in the mould from an old plank.

Lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules Crazy mould patterns.

Crazy mould patterns. Invasive stream inlet in Dead End. This was not responsible for making the passage.

Invasive stream inlet in Dead End. This was not responsible for making the passage. Dead End ends at two digs. The right-hand dig quickly gets very wet, which is presumably why the syphoning hose was there.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules

Dead End ends at two digs. The right-hand dig quickly gets very wet, which is presumably why the syphoning hose was there.

Modelling by Jules, lighting by Tarquin, Pete and Jules The left dig is longer, becoming flat-out for a long distance. None of us wanted to push through it.

The left dig is longer, becoming flat-out for a long distance. None of us wanted to push through it. Stal pouring from a hole in the ceiling. The mud stains are no longer just a historical remnant. This area floods. Severely.

Stal pouring from a hole in the ceiling. The mud stains are no longer just a historical remnant. This area floods. Severely. Worm casts in the mud banks. No worms were seen, but they definitely live here.

Worm casts in the mud banks. No worms were seen, but they definitely live here. The passage then becomes much lower, presumably a former sump. This part can probably flood to the ceiling.

Modelling by Pete, lighting by Tarquin and Pete