Vertical caving terminology and methods > General hardware

Metal links that are a bit bulky but relatively easy to attach/remove from ropes or other metalwork. Used to attach ropes and ladders to anchors, and various pieces of SRT gear to each other. General purpose items that are used in many different situations. Fundamentally, a carabiner is a hook, with a hinged gate on one side to open/close, which closes automatically using a spring, preventing loads from accidentally slipping off the hook. In the vast majority of cases, the gate hinges inwards into the body of the carabiner, but there are some designs where it hinges outwards. This intentionally makes it easier to clip things into a carabiner, than to remove them from it. (If the gate opens outwards, then if the load somehow ends up pulling in the wrong direction onto the gate, it would pull the gate open, rather than closed, so these types are not suitable for caving.) In most designs, the spring is separate from the gate, and normally hidden inside the gate, but there are some designs (such as wiregates) where the gate itself acts as a spring. In the majority of designs, the gate has a standard hinge joint, but in some designs, the spring itself acts as a hinge, and there is no hinge joint (particularly very weak designs made from a single piece of metal or plastic, sometimes found on dog leads or luggage straps). During normal use, the load is positioned on the stronger parts of the hook, not the gate. In all good designs, the gate itself provides some of the strength, with a load bearing latch.

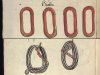

Loads of shapes, but the normal ones are "oval" (actually a straight sided oval, with straight sides and half-circle curves at each end like a capsule or running track, which are better for holding some tyes of pulley), "offset oval" (where the curves on the gate side are more gentle than on the backbone side), "D-shaped" (with sharper corners on the backbone side, and the same size at each end, quite uncommon), "offset D-shaped" (with sharper corners on the backbone side, slightly wider at one end than the other, the most common design), D-ring, "pear-shaped" (like a slice of pizza with the corners curved) and "HMS". HMS is the same as pear-shaped, but slightly bigger so that an Italian hitch can change direction more easily. "Gourd-shaped" carabiners (between a figure of 8 shape and pear-shape, with a wide end, a narrow end, and a narrower waist) are very common for utility purposes, but are almost never used with caving, though they are sometimes sold for holding a belay device. Some may have odd shapes to work better with pulleys or cables.

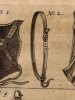

The gate may be "locking" or "snap-link"/"snap-gate" (non-locking). Locking types may be "screw gate" (which do not auto-lock themselves), "twist" (which auto-lock) or have some other mechanism that must be pushed out of the way to open them. Screw gates, when hanging vertically, are normally oriented with the screw gate locking downwards, so that gravity helps keep them locked, with the mnemonic "screw down so you don't screw up". (There are some very specific cases where this is not done, such as when using power tools, since powerful vibrations cause them to move in the opposite direction from what gravity would normally suggest. This exception is not normally relevant to caving.) Auto-locking gates are harder to clip onto things, because they normally need fingers to hold the gate open without getting in the way, but they are immediately locked once the gate is released, which can be safer in many cases. Twist locks can be double, triple or quadruple action (or perhaps higher), requiring more movements to open them, which makes them harder to use, but less likely to accidentally open. Snap-link gates may be "straight" (easier to clip into hangers), "bent" (easier to clip into ropes and a slightly wider opening) or lighter weight "wiregate" (close much faster if they pop open or "flutter" if hit into a surface hard during climbing falls, not important for caving). "Twin" or "double" gate designs have two gates, one opening inwards and one opening outwards with opposite hinge ends instead of a lock, and can be opened by something poking between the gates. The gate normally latches closed with either a nose hook and pin (which snags everything) or "keylock" shape (anti-snag), but "dovetails" (also known as "cross-type", "toothed" or "hook and seat", which snag everything even worse) were previously common. Several designs, each with different names, provide the anti-snag feature with wiregate carabiners. Carabiners without a load bearing latch for their gate have a far lower strength rating, and are not normally used for caving.

Some designs have built in pulleys for running them along steel cables. Some have braking carabiner slots built in. Some have dividers to keep ropes captive at one end of the carabiner or the other, known as a "captive eye" or "captive carabiner". These may have a separate gate for the captive eye. "S-carabiners" take this to an extreme, with an S-shaped body, and opposing gates at each end, but these are almost never strong enough to be used for caving. Some have odd shapes to stop equipment from sliding easily to the wrong end, partcularly ones intended for use with belay devices. Carabiners are typically made from aluminium which is light weight but abrades faster, or steel which is heavier but resists abrasion much better (and generally visibly bends before it fails, which can be a helpful warning at very high loads). Aluminium and steel corrode when exposed to water for lengthy periods. Some are made from stainless steel, which resists corrosion (but often does not bend before failing at high loads). Some are made from titanium, but it is not easy to forge without potential defects, and so most manufacturers do not wish to work with it. They may be made from metal with a round cross section, or an I-beam shaped cross section, or some other weight relieved cross section. This cross section is known as their "stock". Round allows ropes to slide a little more easily over them, perhaps useful for belaying. I-beam and other weight relieved cross sections make the carabiner lighter without initially affecting the strength, but because there is less material, they can wear through more quickly when muddy ropes slide through them a lot, though this is not much of a problem with steel carabiners.

Carabiners are normally designed only to be pulled in two directions at once, directly opposite each other, along the length of the carabiner. It is common to clip a carabiner into two ends of a sling which is looped around a natural, with a rope pulling on the other end of the carabiner, and as long as the two ends of the sling approach the carabiner from a similar direction, this is considered acceptable. However, if they approach the carabiner from very different directions, this puts a three directional pull on the carabiner. Most carabiners are not actually designed to be pulled in that way, and this can reduce their strength significantly. D-ring carabiners are one exception to this, as they can be loaded in a range of directions over 180°. Oval carabiners can often cope with a fairly significant three directional pull without a significant loss of strength, but this depends on how far apart the pull directions are. With other common designs of carabiner, the sling can easily end up pulling on the gate, which reduces the strength to the same as if the carabiner were loaded sideways. If the three directions are very far apart, it can experience a much higher force on the gate than the load that it is holding (just like a Tyrolean traverse), so it can fail at surprisingly low loads. In such cases, having the sling ends at the hinge end of the carabiner normally allows it to cope with significantly more load than if they are at the nose end of the carabiner, but it is much better to use a more appropriate design of carabiner that is designed to be loaded in three directions.

Some designs of carabiner exist for rigid webbing, commonly seen in paragliding equipment. These have square shaped or flat ends, and while these may look better for using with slings, they do not work well with the flexible webbing used for most slings. In use, the sling slips to one side of the flat surface, and pulls much harder on the gate side of the carabiner. They are not designed to be loaded that way, and will fail at much lower loads than they are rated for. These carabiners can only be used with very specifically made webbing designed to be rigid, with exactly the right widths, and should not be used for standard slings. As a result, these carabiners are not generally suitable for caving purposes.

PPE rating for the minimum breaking strength (MBS) of carabiners is 20 kN in most cases in Europe and 22 kN (actually 5000 lb) in the USA, but the European standard EN 12275 requires 18 kN or 25 kN for some designs. As a result, most carabiners can hold 2.2 tonnes or more (actually given as a breaking strain of 22 kN) when loaded correctly, or 0.7 tonnes when loaded incorrectly, such as sideways, or with the gate open. Carabiners usually have the ratings for loading in the correct direction, loading sideways, and loading in the correct direction with the gate open, stamped onto the carabiner itself. 2.2 tonnes is the weight of two small 5-door 5-seater family cars, or 4'279'174 baked beans. Thick steel carabiners might be able to hold 4.5 tonnes, just in case you ever needed to hang a Red Arrows hawk off the wall of a cave. There are some extreme models that go as high as 7.1 tonnes, enough to hold an entire double-decker bus worth of passengers, an 89 cm sphere of gold, or about 65'000'000 worker bees, assuming they have not gone extinct by the time you read this. These ratings apply to new carabiners, not ones that have been abraded, scratched and battered through years of use, or corroded by exposure to water. While there are many lower quality carabiners produced for a wide variety of purposes, including dog clips, keyrings, camping equipment and novelty toys, these should never be used for caving. There is a chance they could be mistaken for a PPE rated carabiner, and used in a situation where reliable strength is essential, and they are unlikely to cope with the rigours of caving anyway. They are sometimes included when purchasing equipment online that claims to be PPE rated, such as multi-purpose ropes. In such cases, the carabiners absolutely must not be trusted (and the other product's PPE rating should be considered either fake, or highly suspect, if it is being sold with non-PPE carabiners). If a carabiner does not have the correct ratings properly stamped into its metal, it is likely to be fake, and must not be trusted.

In case you are wondering about which spelling to use, "carabiner" is the dominant spelling but "karabiner" is valid. The original word is German, where it is commonly spelled "Karabinerhaken", meaning a "carbine hook", a hook for a type of rifle. However, even in German, it was originally spelled "Carabinerhaken", and the "k" is a relatively recent change, with the older spelling still remaining in current use in southern Germany, Austria and Switzerland. This got shortened to just the name of the rifle. The name of the rifle is spelled "Karabiner" or "Carabiner" in German (with "Carabiner" being the original spelling), "carabine" in French and "carbine" in English. The word originates in French, not German. The name of the soldiers who used them is "Karabiniers" or "Carabiniers" in German, "carabinier" in French, and either "carabineer" or "carabinier" English. The metal link was used by British cavalry carabiniers for centuries, and already had 4 English names before anybody decided to use the German one. The name of the metal link is "Karabinerhaken", "Carabinerhaken", "Karabiner" or "Carabiner" in German and "mousqueton" in French (meaning "for a musket"). Spanish and Italian, rather unsurprisingly, follow the French spellings in all cases, changing only the word endings according to the rules of each language. Dutch follows German, with "karabijnhaak". So it really does depend on whether you like to use the original French name for a type of rifle, the Germanised spelling for the rifle, the Anglicanised spelling for the rifle (or the Hispanised or Italianised, for that matter). With English being a Germanic language with very heavy Romance (French and Latin) influence in the spellings of more than half of its words, there could be arguments for both. English is three times more likely to use a "c" at that position in a word, just as it is with the name of the rifle and the soldiers who used them, and how you don't drive a "kar", or use batteries containing "kobalt", or call the animal a "kat" (even though the word "cobalt" also comes from German, where it is spelled with a "k", and "cat" is also Germanic, which German spells with a "k"). However, some people like to use a "k" to make it feel extra German, just like the "ö" in the British band "Motörhead", and the distinctly German sounding Berghaus, and Möben Kitchens, which are both British companies. German makes some people assume that outdoor equipment will be engineered better for outdoorsy purposes, apparently. If that was confusing, just read the first sentence of this paragraph again. Oh, and it's easier to make jokes about how "[someone] has crabs" if you use a "c".

Incidentally, it is not known how the rifle got its name, but it might be the Latin name for the scarab beetle, "scarabaeus", which comes from the Ancient Greek "κάραβος" meaning "beetle". Other words with that origin include "crab" (rather appropriately), "crayfish" and "scorpion", just in case you needed more evidence that a "c" was more appropriate. Those might come from the Arabic "عَقْرَب" meaning "scorpion", "قَارِب" meaning "to approach" or "خَرَبَ" meaning "to ruin".

Pinned mortice and tenon joints (how carabiner gates are connected) first appeared in wood, with the earliest known example dating from 5099 BCE in what is now Germany, used for lining a well. Bronze bangles (bracelets) were made in Brittany, France in 1450-1300 BCE, which have a hinged gate with a mortice and tenon latch, held closed with a pin. They did not spring closed, and the shape would allow loads to rest on the relatively weak gate, but they are otherwise impressively similar to a modern carabiner. Other designs relied only on pinned mortice and tenon latches. They were presumably created by the Armorican Tumulus people. This incredible find was reported in "Nordez, M. (2023). Metal hoards in a ritual space? The Atlantic Middle Bronze Age site of Kerouarn, Prat (Côtes-d'Armor, France)". This approach had spread to Austria, Switzerland and Britain by 400-200 BCE. Fibulae brooches that worked almost identically to a safety pin, had appeared as early as 1400 BCE in Mycenaean Greece, and designs are still used today. Unlike a carabiner, the spring tries to open the gate, and it needs to be manually closed. Greek earrings from 400-200 BCE and better versions from 200-1 BCE used the same approach. Roman padlocks had large locks that had to be manually assembled to close them, rather than the hinge and spring of a carabiner gate. Rings almost identical to the non-hinged Brittany bangles, which may have been slave shackles, were also identified as Roman, but their origin and age is unknown. Neither half of the ring could be used without the other, unlike a carabiner's hook and separate gate. Lombard earrings from around 750 CE used the same principle as the safety pin, in Cividale del Friuli in northern Italy. Oval links that look almost exactly like an oval carabiner, were in use by the Landshut Armoury in 1485, in Bavaria-Landshut, Holy Roman Empire, now Germany, depicted in the Zeughausinventar von Landshut by armory master builder Ulrich Pesnitzer. These had a removable mortice and tenon gate, presumably using pins at each end instead of a hinge and latch, and could function as a hook without the gate. These were used as a removable link which could be connected to a rope, just like a modern carabiner. They almost certainly did not have a sprung gate, so they would not normally be considered to be a carabiner, and were called "hagken", an older spelling meaning "hook". The Landshut Armoury also had gourd-shaped solid chain links, which could be used to attach a chain to a rope or other objects, and were used to connect them to parts of a horse-drawn gun carriage. Similar chain links had been used during Roman times.

The metal clips that were the original carabiners, were first depicted by Knight Martin Löffelholz von Kolberg in about 1505 in the Löffelholtz-Codex, with a sprung gate made from the spring itself, without a load bearing latch, very similar to the fibulae brooches. They were shown as part of a bridle/muzzle for horses, where they were riveted directly to the leather (a design that remains in use today). They were also depicted as a way to connect reins to a horse's bit, using a snap hook design with a captive eye which a strap could be attached to. Both designs were used in the Nürnberg (Nuremberg) region of the Holy Roman Empire, now Bavaria, Germany, and were referred to as a "hack", meaning "hook". German artist Albrecht Dürer, who painted knights, horses and their equipment extensively in the Nürnberg region at the same time, apparently did not paint anything similar, suggesting that the carabiners were something very uncommon, and are likely to have been a new invention.

Captive eye carabiners then appear to be depicted, along with separate swivel joints that they clipped into, in the connection between a horse's curb bit shank and reins in Napoli (Naples), Kingdom of Naples (now Italy), depicted by Federigo Grisone in the 1570 edition of Gli Ordini Di Cavalcare, during the Italian Renaissance. The carabiner shown is long and thin, with a rounded main body, and a gate made from the spring itself. The same depiction also shows an alternative version using a shackle instead of a carabiner, and another showed basic hooks, suggesting that the carabiner was a relatively recent change in that area. (Shackles can be seen in curb bit designs from the Holy Roman Empire, now southern Germany and eastern Germany, from 1600-1650.) I could not find any surviving examples of early carabiners from horse tack in any museum collections, despite a very large number of curb bits, snaffle bits, muzzles and associated horse armour surviving from that era, so they are unlikely to have been in common use.

Swivel joints are rarely used for caving carabiners, but they were of great importance for early carabiners, and are still seen in many carabiners used for industrial purposes, and for less demanding uses such as bag straps. The swivel joint itself had developed as the axle of a potter's wheel, which appeared in Mesopotamia (now Iraq) around 4200-4000 BCE. For metalwork, it can be found in Egyptian rings from 1991-1802 BCE. Swivel joints had appeared in the connection between a horse's bit and its cheek pieces around 900-800 BCE in Luristan (now Iran), an approach that reached Villanovan/Etruscan Italy as early as 800-700 BCE, and then spread to Greece and what is now Germany. Ancient Greeks and Romans used swivel joints with a limited range of motion in door hinges, from as early as 800-400 BCE. Well developed swivel joints were commonly used as parts of Roman manacle shackles throughout central Europe during the Roman Empire, starting from 100 BCE, with a few examples from eastern France, a couple from northern Germany and at least one from northern Italy. They were used to connect chain rings in Britain around 43-410 CE, and are thought to be Roman in origin. Swivel hooks have been found dating from Medieval Britain (after the end of the Roman occupation) and other parts of Medieval Europe, and while the exact date or location of their origin is not known, a well dated German example is from 1250. Swivel hooks might be used to hang pots above a fire. Swivel joints can also be seen in the connection between a horse's reins and bit shank in curb bits from 1325-1350 in Napoli, now Italy, an approach which spread throughout Germany and France, and can be seen in numerous other examples.

The metal clips were then adapted as a way to hold cavalry weaponry, and the specific device that gave carabiners their name was used to clip a carbine rifle to the leather shoulder strap of cavalry carabiniers. While they are usually stated as having their origins in the Napoleonic Wars, they had in fact existed for at least another two centuries before then in Britain, the Dutch Republic, Spanish Netherlands (now Belgium), Sweden and Austria, as well as the parts of the Holy Roman Empire that subsequently became Prussia and Germany. They were originally known as a "swivel" in English (spelled "swivell" in the 17th century), since they formed part of a swivelling connection to the shoulder strap, and were presumably developed as an adaptation of a swivelling hook. Swivel carabiners for weaponry are now often called a "spring clip" by historians. (The shoulder strap was originally known as a "swivel belt" and later "carbine sling" or "baldric" in Britain, "Karabiner-Bandelier" in German, and "banderole porte-mousqueton" in French.) Graeme Rimer, former curator of the British Royal Armouries stated (personal correspondence) that swivel carabiners are likely to have first appeared in Britain around 1600 at the earliest, but that the exact date is not known. At that time, they would have been used with an arquebus (a longer version of a carbine), by a harquebusier. In particular, it was the cavalry that would use them, since the spring loaded gates would not pop open from the movement of a horse. The vast majority had a separate flat spring instead of the gate being made from the spring, and this required them to have a teardrop shape, so that the spring could have something to push against. Their original use with horse tack had already been largely replaced with buckles.

The first time carabiners for holding weaponry are thought to have been depicted is in a series of paintings by Flemish artist Sebastiaen Vrancx, between 1601 and 1615. They are shown as being used by cavalry harquebusiers on both the Flemish (now Belgium), and Dutch Republic (now Netherlands) sides of a series of battles. At the time, the Flemish side was part of the large territory owned by Habsburg Spain called Spanish Netherlands, and the Dutch Republic was still trying to break free from it. However, even though the Spanish infantry fought alongside the Flemish militia, a Spanish book about military tactics published just two years earlier makes no mention of carabiners, and instead describes how an arquebus needed to be held in the hands while on horseback. As a result, they seem not to have been used within Spain at that time. Two of the paintings were made between 1601 and 1615, one of which depicted the siege of Oostende (Ostend) that took place in 1601-1604, and one was made before 1610. As with many of his later paintings, the existence of the carabiners is implied in two of them only by the arquebus being slung behind the back on a shoulder strap, in an arrangement that would have needed some kind of attachment. However, one of the 1601-1615 paintings clearly shows a carabiner on a Dutch Republic harquebusier, though the details are hard to see, and the arquebus is not clipped to it. It is clearly fixed to each end of the shoulder strap, and could not slide up it. It is not clear enough to see if it had a swivel connection, but it probably did, given its similarity to later designs. At that time, the Dutch Republic had only just stopped being an English Protectorate, but the design is quite different from most of the British ones. In all paintings, only one or two harquebusiers have shoulder straps, and most resort to holding the arquebus in their hands, suggesting that carabiners were expensive or relatively new, and only a lucky few were able to use them. It is quite possible that only mercenaries hired from the Holy Roman Empire originally had them, which would explain their low numbers, and would also explain how the idea got from the Holy Roman Empire into Flanders and the Dutch Republic. It was only later that Sebastiaen Vrancx would serve as a captain for the Antwerp civil militia, but his incredibly detailed earlier paintings had clearly been taken from direct observation of the local military, and he had presumably travelled to see the siege of Oostende in person as a tourist, like many other people.

Sadly, there is no further known evidence to help work out which country they originated in, or exactly when. Other artists did not seem to notice them, even when depicting military equipment in the areas where they were being used. The Riding School or Exercise of Cavalry, a collection of prints by Jacob de Gheyn II from the Dutch Republic in 1599 showed harquebusiers without swivel carabiners. Wapenhandelinghe van Roers Musquetten ende Spiessen, a detailed book by the same author in 1607, showed a series of military drills, but did not show cavalry or any swivel carabiners. They were also not shown in Jost Amman's illustrations, such as in the 1529-1579 editions of Catalogus Gloriae Mundi by Barthélemy de Chasseneuz, or the 1596 Kriegßbuch volume 1 and 2, which were published in Holy Roman Empire, not far from where the earlier horse tack carabiners had been recorded. In 1611, an Italian military instruction manual written by a knight from the Duchy of Milan (now Italy) who was serving the Habsburg Spanish in the Spanish Netherlands, showed the uniform of a harquebusier and described how an arquebus was carried using a shoulder strap. The illustration showed only what looks like a fabric loop in the shoulder strap which appears to be looped over part of the arquebus, and did not clearly show a carabiner, but this is likely to be a mistake by the illustrator, who would not have known what they were depicting. The manual was published in the Spanish Netherlands, now Belgium, in spite of being written in Italian.

The earliest known definitive mention of carabiners for holding weaponry is from 1616 in Kriegskunst zu Pferdt by Johann Jacob von Wallhausen, in what was then the Holy Roman Empire, later Prussia, now Germany. What have the Romans ever done for us? (It should be noted that the Holy Roman Empire was not actually very holy, it was not Roman in any way, and it did not operate like a normal empire.) The diagrams look a little badly drawn, and are depicted and described without a swivel joint, but the description clearly talks about a sprung gate. (His books were known to have numerous publishing errors from being rushed to print too quickly, and illustration mistakes are hardly a surprise.) If they did not have a swivel, then they will have been captive eye carabiners instead. Swivel carabiners were clearly depicted with a sprung gate and swivel connection in the Dutch Republic in 1624. The distinctively shaped design is almost identical to the one depicted by Sebastiaen Vrancx, but could now slide up the shoulder strap. They are depicted in Swedish uniforms from when they took part in a battle during the Thirty Years War in 1631, and they may have had them prior to that. The design has a sprung gate and swivel connection. Mercenaries from the Holy Roman Empire (described as German) who fought for Sweden during the Thirty Years War are also depicted with the same design. They were not depicted as being used by the French cavalry of that era. Swivel carabiners were mentioned in British cavalry instructions by John Cruso in 1632 and depicted in illustrations that accompanied that publication. They were described only as a "swivell" that was attached to a belt, as if they were something already considered normal.

The earliest surviving examples of British carabiners, which are also the oldest known surviving carabiners of any kind, date from 1640 (British Royal Armouries Collection, XIII.298), at which point they were in common use with the British cavalry. They appear to be the design depicted by John Cruso, being teardrop/pear-shaped with a swivel connection. They had a sprung gate, but did not have a load bearing latch. Some had a notch that caused the gate to align correctly from side to side (two different designs can be seen in Littlecote The English Civil War Armoury, Thom Richardson and Graeme Rimer, 2020). The same designs were used in 1650, at the end of the English Civil War. Virtually identical designs are still in use today on handbag straps, luggage straps and ID lanyards (usually without the strap roller). Another British design had a captive eye connected to a swivel joint, and the strap connection was riveted on, instead of being able to slide up the strap. It had a sprung gate, but does not have a load bearing latch. This approach is not as useful as the design that can slide up the strap, and may be an earlier design predating 1640, or may have been a ceremonial design. It is almost identical to the early Dutch Republic design depicted by Sebastiaen Vrancx, and could in fact be one of those. The specific example depicted was probably issued in 1641 for ceremonial (knighthood) purposes only, but a second example of that same design from Browsholme House which saw actual service, clearly seen in Military Illustrated issue 95 (April 1996), may be from 1655-1675, based on the date of the coat it was associated with. Swivel carabiners can be seen in depictions of Austrian cavalry in the Thirty Years War which lasted from 1618-1648, but the first documented use of them was around the middle of the century, near the end of that war, and it is not known if they had them any earlier than that. (They are not shown in a depiction of a mounted harquebusier from Austria shortly before 1600.) While one is displayed at the Austrian Museum of Military History as part of an Austrian cavalry uniform from 1620, the museum stated (personal correspondence) that they do not actually have any surviving examples from 1620, and the carbine it is associated with has been dated to around 1650. They do not know if the carabiner is a replica made in 1860 (when the display was assembled) or an original piece from 1650, but its condition suggests that it is a replica, so its accuracy is unknown. However, they do have another example from around 1650, and that could have been used to make the replica. It is an asymmetric teardrop shape (very similar to a clothes hanger hook), with a sprung gate that has a tongue to stop it opening in the wrong direction, and has a swivel connection, but does not have a load bearing latch. Swivels were mentioned in a British royal declaration in 1682 and 1683. By 1683, Austrian imperial cuirassiers had fancy back-to-back swivel carabiners (like a Petzl Freino), but still without a load bearing latch.

Swivels were then mentioned in legal documents in the British province of Massachusetts (now USA) in 1699, and in various other British American colonies in the early 1700s, without any description of their design. The first time the compound word "Carabinerhaken" is known to have been published is in a 1712 encyclopedia from the Holy Roman Empire (now Germany). The spelling "Karabinerhaken" was then used in a 1773 encyclopedia from the same country, with both spellings remaining in use today. They were mentioned as having sprung gates by British military author Humphrey Bland in 1727, the Army of Great Britain in 1728 and Captain Hinde in 1778. Austrian cavalry are depicted with swivel carabiners in 1734 during the War of the Polish Succession, from 1748 to 1780 covering the Seven Years War with Prussia, in 1757, and contemporary military depictions of a 1767 uniform. The 1767 version is not clear enough to tell if it had a captive eye, but much clearer pictures show only the more basic swivel carabiner being used at least up to 1780. Swiss examples from 1767-1782 do not have a load bearing latch, and are very similar to the British designs from 1640. British cavalry swivel carabiners from 1768 are depicted with a captive eye attached to a chain, which in turn connected to a swivel joint. They still did not have a load bearing latch, and the gate itself appeared to be made from the flat spring. The same approach ended up in the USA, but with the more common type of gate. Prussian cavalry swivel carabiners from 1785, do not appear to have load bearing latches or captive eyes at that time. The British Napoleonic Wars swivel carabiner design was established in the early 1790s, with a captive eye, spring loaded gate and a load bearing dovetail latch. Pierre Turner documented them from surviving 1815 cavalry equipment, in 2006. The load bearing latch was a significant advance that typically triples the strength of a carabiner, and would allow them to be strong enough to reliably hold a person in future. Dovetail joints had been used since 1991 BCE with wood in Egypt, and as metal bow-ties used to join stones since 1450 BCE, an idea which spread around the Mediterranean and Asia over the next thousand years. Dovetail joints appeared in Britain in 1650 and were famously used to join large metal parts on the Iron Bridge in 1777-1779. However, milling them into a small piece of metal that would subsequently be bent into the perfect position where a hinged joint could always line up perfectly with it, became a lot easier during the Industrial Revolution. It seems likely to have originated in Britain. No examples from the earlier American Revolutionary War allowed the design to be seen, but it is unlikely that a dovetail latch existed then, because it was not subsequently used in America. Pierre Turner also depicted a variation of the 1790s carabiner design that had a divided body, with a long pin that was attached to the back of the gate, and pushed through a hole in the spine of the carabiner when the gate was opened. Its purpose was probably to keep the gate aligned correctly, and prevent the spring from being damaged, but it might have also made the carabiner less likely to accidentally open. It would have made it awkward to open intentionally, and as a result, this is the only time this design has been seen. In 1798, fire brigades in Leipzig, Holy Roman Empire (now Germany) were using hooks attached to their belts to hold on to a ladder while climbing. No further details are given about the hooks, and they are likely to have been a simple hook, not a carabiner. German travel writer Philipp Andreas Nemnich wrote about single and double models of swivel carabiners being produced in Wolverhampton, Britain, in 1799.

Initially, their use was confined to the cavalry-related purposes for which they were created. During the 1800s, they were finally used to clip other things to each other, or to belts, just like we do today. One example is that British naval sword belts started to use them from some time around 1803, without a load bearing latch or captive eye. French cavalry were using swivel carabiners around 1804, which had a sprung gate, but did not have a load bearing latch or captive eye. These are likely to have been German in origin, since France had taken over parts of Germany by then. Bavarian cavalry (therefore including the München area) are depicted with swivel carabiners in 1806, during the Napoleonic Wars. In 1830, Italian manufacturer Giuseppe Bonaiti (later called Kong) started making swivel carabiners (referred to as musket hooks, a translation of their Italian name), making them the oldest known carabiner manufacturer that still makes carabiners, for two centuries! By 1833, the mining industry in Britain was using extremely strong hooks with springs to keep them closed, the first time a spring hook was mentioned in relation to mining. Being able to hold as much as 3 tonnes during normal use, these were not the normal carabiners of that era, and were certainly much more significant spring hooks. They were the first spring hooks known to be capable of holding a person, and were far stronger than modern rated carabiners, but are likely to have been much too large and heavy to be used as a normal carabiner. Over time, more normal carabiners started to be used in the mining industries of other countries, but it was not until over 30 years later that spring hooks were mentioned in relation to the German mining industry.

The fire brigade of Berlin, Prussia (now Germany) was among the earliest to use carabiners, being well established by 1847. Initially, they called them "Gurthaken" or "Gurthacken" ("belt hook"). They were used as an equivalent to a cows tail. No other uses were stated at the time, but they had to be able to support the weight of a human, and they are the first known carabiners to be capable of that. The design, known as the "Berliner Gurthaken", can be seen in an 1850 publication and an 1877 publication, and had to be large enough to fit over the rung of a ladder. Rather unusually, it did not have a captive eye at one end (unlike most subsequent designs), because it had a leaf spring inside the loop of the carabiner, which effectively divided the carabiner in two, and got in the way at one end of the carabiner. The gate, which did not have a a load bearing latch, was hinged next to the spine of the carabiner, and this prevented loads from being hung from that end of the carabiner. So the captive eye was a long slot in the spine of the carabiner, which had a strap from the belt passing through it, so that rather than being a proper cows tail, it forced the belt to be right next to the ladder that it was clipped to. In 1849, American Walter Hunt reinvented the safety pin, which may not be a carabiner, but its design is very similar to the first wiregate carabiners. And the United States Patent Office accepted it, even though it was virtually identical to several fibulae brooches created 3200 years before. In the same year, Charles Rowley independently reinvented the safety pin in Britain, and the British patent office also accepted it as a new invention. Patent offices don't seem to be particularly meticulous when it comes to detecting prior art. There is the suggestion that Charles Rowley invented it long before Walter Hunt, and took too long to register the patent, but the reality is that both of them were 3200 years too late for it to have been an original invention. An extremely well developed British swivel carabiner had a small captive eye at the narrow end, a sprung gate, and a load bearing dovetail latch. This, and the fact that it was connected to a chain, make it likely to be from some time after the 1790s, in spite of it being provisionally dated to the 1600s. The sling colours and insignia match the Royal Welch Fusiliers from 1850-1915.

In 1851, fire brigades in Ulm, German Confederation (now Germany) were using small carabiners 7.5 cm wide and 2.5 cm long, to clip ropes to their belts to leave their hands free while climbing. The design was extremely similar to the old carbine rifle carabiners, with a captive eye and a flat spring visible inside the carabiner's main loop. The carabiners were not load bearing, without a load bearing latch, and were only used for temporary storage. By 1855, fire brigade carabiners were referred to as "Karabinerhaken", and they were already referred to as "rescue carabiners", so they may well have served other purposes too, such as for lowering people. American carbine sling swivels from 1855-1865 (including the American Civil War) had captive eyes and spring loaded gates, but used a basic tongue instead of a load bearing latch, though versions imported from Britain had a dovetail latch. By 1859, the Austrian (at that point a part of the German Confederation) fire brigades were using carabiners. An 1859 design by American Morris Pollack used an S-shaped body with opposing gates at both ends that opened at the same time as each other; the first S-carabiner. Carabiners were used to support a person as part of several commercially available fire escape descenders, starting from 1860 in the USA, with many different designs being used, often based on the old swivel carabiners. From as early as 1861, Austrian fire brigade suppliers such as Wm. Knaust from Vienna (who later supplied the mining industry too) incorrectly called them a "Carabiner", meaning "carbine rifle" instead of the more correct "Haken", meaning hook. This is the first time the modern name is known to have been used, and it was spelled with a "C". Carabiners were used in American Civil War cavalry link straps (for linking horses together) in 1861. During that same war, the older design of swivel carabiners also started to be used for holding the drums of American military drummers, replacing the hooks and tied straps that were used during the American Revolutionary War.

Carabiners then rapidly expanded into numerous designs for a variety of purposes, and started to be called "spring hooks", "snap hooks" or "safety hooks". Many patents show smaller models, designed for lightweight tasks (such as connecting a strap to a handbag) or for connecting ropes and straps to animals, including horse tack again. Most of these are not relevant to caving, except the handbags, of course. A proliferation of spring designs then appeared, only a few of which are important here. An 1862 design by American Robert A. Goodyear had a hidden spring. An 1863 design by American Norman North had a gate spring pushing on a hidden lever, like a modern carabiner. An 1863 design by American Samuel Babcock had a flat spring hidden inside the gate. An 1864 design by Americans R. E. Gorton and A. Gorton had a hidden compression spring (like a modern carabiner) hidden inside the body of the carabiner, as well as a dovetail latch, the first time it was depicted in America. This idea was registered again in 1889. An 1864 design by American Oliver S. Judd used a torsion spring like a safety pin.

Around 1864, a new design of carabiner emerged in Leipzig, Kingdom of Saxony, German Confederation (now Germany), which became known as the "Leipziger Gurthaken", the Leipzig belt hook. It had a captive eye, covered torsion spring, did not have a load bearing latch, and was extremely large, so that it could fit over thick ladder poles rather than rungs. Though the size is not stated explicitly, a later description appears to refer to it, saying that it was 19 cm long and 12 cm wide, and made by Reichenbach. This was being purchased by fire brigades in Berlin around the end of 1864. In that same year, German and Austrian fire brigade suppliers attended a trade fair in Leipzig, and this seems to have spread the idea of hidden springs to other manufacturers. In 1865, fire brigades from Leipzig were using carabiners with a captive eye, a swivel joint, and a gate (referred to as a "barb") which did not have a load bearing latch. They were expected to hold 200 kg without bending, and will have been very large and heavy. There were two models, one with a traditional flat spring visible in the middle of the carabiner's body, and a more expensive one with a bent flat spring next to the gate's hinge, which pushed it closed. While the spring could probably be seen, it did not waste space inside the carabiner. This was the first design that German fire brigades referred to as an "internal spring", and avoided the damage and associated repairs that resulted from ropes and ladders rubbing against exposed springs. However, the spring was fairly weak, which could be problematic. The origin of the design is not known, or which design was actually developed first, but the design known as the "Leipziger Gurthaken" is the one that became used elsewhere. The terms "Karabiner", "Karabinerhaken", "Sicherheitshaken" ("safety hook") and "Gurthaken" were all used to refer to carabiners. In addition to previous uses, they were used to lower a firefighter out of a building on a rope by clipping the end of a rope to their belt, or to join ropes by clipping to a ring attached to one end of the rope. Firefighters also used them to clip a fire hose to their belt, leaving their hands free to climb a ladder.

In 1868, fire brigade manufacturer Conrad Dietrich Magirus, who ran Magirus in Ulm, Kingdom of Württemberg (now Germany), developed the gourd-shaped carabiner, which became known as the "Ulmer Gurthacken" or "Ulmer Gurthaken" (the "Ulm belt hook"). While many earlier designs remain in common use, this is the first design of modern carabiner to remain in very common use today (though not within caving or climbing), which is immediately recognisable as a normal carabiner, rather than a spring hook, dog clip or luggage strap clip. One reason for the change is that the gourd-shaped carabiner could be removed from the belt when the belt wore out, and moved onto a new belt. They were the first type to hide a compression spring inside the gate like a modern carabiner (known in German as "Innenfeder", an "internal spring"), to prevent the spring being damaged by the rope. Initially, they did not have a load bearing latch, and they were available in three sizes, a small one to connect ropes to each other or to a belt for storage, a medium sized one to clip over the rungs of ladders with two poles, and a larger one to clip over the larger pole of single-pole ladders. The sizes were not explicitly stated, but they were likely to have been 9.5 cm, 15 cm and either 18 or 19 cm, judging from diagrams and the sizes sold later. The metal is likely to have been 13 mm thick on the smallest size, and 14 mm thick on the larger sizes. In spite of the gourd shape, they were often confusingly described as being round. Fire brigades in München, Kingdom of Bavaria (now Germany), were already recommending the gourd-shaped design by 1869. A swivel carabiner from the Netherlands in 1868 had a captive eye, with a chain connecting it to the swivel joint. The gate had an alignment tenon latch on the front of its tongue that was load bearing, but likely to be less effective than a dovetail. It is not known when this design appeared, since it is the only surviving example in the Dutch military museum collection. An oval link with an outwards opening gate was patented in 1868 by American William N. Pelton, with a load bearing pin that locked the gate, designed to connect snow chains to wheels. The gate was not spring loaded, so it would not normally be considered to be a carabiner. This almost exactly matches the design from 1485. An 1868 design by Americans William Cooper and William D. Rumsey used the same approach as a modern dog/trigger clip, and subsequent designs quickly became shaped more like dog/trigger clips.

In 1872, gourd-shaped carabiners developed by Magirus were being sold in Vienna, Austria, Austro-Hungarian Empire, by Franz Kernreuter, intended for use by fire brigades. Hungarian fire brigades used the Leipzig design of carabiners in 1874, whose lengths were not stated, but the internal circumference (presumably of the main ring) was stated as either 37.5 cm or 55 cm, which correspond to about 20 cm and 26 cm in total length! In that year, fire brigades from Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Empire and München, Bavaria, German Empire (now Germany) used the term "Carabiner". In the same year, Austrian fire brigades were using the small carabiners on the end of a rope as a way to attach the rope to a wall hook, by looping the rope through the hook, and clipping the carabiner back around the rope, so that it only had to support half of the total load. In 1875, the Leipzig carabiner was already treated as an older design by German fire brigades. By that stage, they had already been using ropes with carabiners attached to both ends, to allow ropes to be quickly chained into longer lengths, or connected to an attachment. In 1877, Magirus (whose city of Ulm was now part of the German Empire, thanks to the chaos of German state history) stated that they had now adopted the dovetail latch into the gourd-shaped carabiners, which they called a "Zahnschloss" or "tooth lock". Initially, this was developed for smaller carabiners, but was then used on the larger carabiners within the same year. Their approach was exactly the same as the British design from about 85 years earlier (though much easier to do with the thick metal used for fire brigade carabiners), and could be made with as few as 7 cuts. This is how almost all dovetail latches are still made. Conrad Dietrich Magirus stated that they had also tested carabiners with a pinned latch. No details are given of how the pin worked, but it could be that he was referring to the tenon latch used in the Netherlands in 1868, or it could be that they had developed the nose hook and pinned latch which is used today, but either way, they could not make it strong enough in 1877. Magirus had tested iron and mild steel carabiners, both with and without the dovetail latch. Without it, iron carabiners already elongated by 1 mm at 100 kg, permanently stretched 1 mm after loading at 200 kg, and unrolled at 600 kg, while steel carabiners elongated by 1 mm at 200 kg, permanently stretched 0.5 mm after loading at 300 kg, and unrolled at 800 kg. With the dovetail latch, steel carabiners did not even start to elongate at 800 kg, showing the dramatic change in strength that the load bearing latch provided. These tests were done using carabiners that had a 9.5 cm external length, 7 cm internal length, and had metal 13 mm thick. A modern (non-PPE) gourd-shaped carabiner made from a similar mild steel, 13 mm thick, could hold 2.4 tonnes! In addition, the dovetail latch stopped the gate from slipping sideways out of position. In 1877, gourd-shaped carabiners were still being sold in Vienna, and used by fire brigades in Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Empire. They were stated as being able to hold 100 kg without bending, so they presumably did not have the load bearing latch yet. Walser from Pest (now Budapest), Hungary, also sold carabiners for the fire brigades in 1877, and these may have been the Leipzig design. An 1877 design by American Lewis E. Walker had two opposing clips with the same orientation, a variation of the S-carabiner.

In 1878, Fire brigades from the Stuttgart region of Germany were using their large carabiners as a descender for abseiling, using a carabiner wrap. They are depicted as using the Leipzig carabiner design from 1864, even though it was already out of date by that stage, so either they were still using the old design, or the drawing is from several years earlier, perhaps before the gourd-shaped design took over in 1868. They would use carabiners to connect ropes to supports held up against a window frame. They would join ropes together using relatively small carabiners. They would have carabiners on belts and sit harnesses, which could be connected to the end of a rope, and used to lower people from a building. They used carabiners in the same way for lowering furniture. Carabiners were a major part of the fire brigade toolkit, and they were available in big and small designs, each strong enough to support a person. In 1879, German mountaineer Carl Seitz of the German and Austrian Alpine Association climbers/mountaineers, was using belts with carabiners, based on the fire brigade designs, to allow people to easily connect and disconnect from ropes when taking tour groups over icy mountains in the Alps. This is the earliest known use of carabiners by mountaineers/climbers, but it is quite likely that others had already been using them, without there being any known surviving documentation of it. In 1880, the Austrian fire brigades were shown using traditional teardrop/pear-shaped carabiners with a captive eye, but this is likely to be an older illustration. An 1880 design by American Joel Jenkins made the entire "snap hook" out of wire, so a wiregate and also a wire hook, following the approach of a safety pin. By 1881, the German and Austrian Alpine Association were recommending the use of carabiners for connecting to ropes, which they obtained from Joh. L. Petzl (no relation to the current company Petzl) in Vienna. They would use them in an emergency to retrieve someone who had fallen into a crevasse. The carabiners would have their club initials hammered into them, for identification. An 1881 design by Canadian Charles Barlow was intended to be used for lowering someone out of a building, as a fire escape. An 1882 design by the German Lohner brothers, made for the fire brigades, had a load bearing dovetail latch, and a pulley with a braking lever, which could be used as a descender or like a mechanical belay device! In 1882, climbers from the German and Austrian Alpine Association climbers/mountaineers were purchasing fire brigade ropes with carabiners. An 1883 design by American Oliver Benson used an S-shaped body with opposing gates at both ends that opened at the same time as each other; another S-carabiner. A design patented in 1883 by American Luke Chapman worked exactly like a modern screw gate, with a screw sleeve on a threaded gate. The patent also states that the sleeve could be put on the body of the carabiner instead of the gate, but that it is preferable to have it on the gate. By 1884, the German mining industry was using carabiners attached to a miner's belt to connect them to ropes for safety. The publication does not show them, but shows a few of the spring hook carabiners that were in use with German mining. An 1884 design by American James H. Farmer also had two opposing clips with the same orientation. Subsequent patents used the exact same approach, and did not deserve to be granted a patent. By 1885, German fire brigades in the München area were using carabiners that were 19 cm long, presumably gourd-shaped. That year, the German and Austrian Alpine Association were complaining that carabiners could open when pushed against the rock, if they had been used for a while. A pair of designs, one oval and one with a captive eye, both created in 1886 by American Edward H. Smith had a spring loaded pin lock, like EDELRID's Pure Slider lock.

By 1887, carabiners were used by the German and Austrian Alpine Association climbers/mountaineers. Ropes with carabiners attached were stocked in Alpine huts in what was then Austria, now Italy. These will have been basic gourd-shaped carabiners with dovetail latches, made from mild steel, and not very strong. A typical strength was 100-120 kg. These continued to be used by climbers/mountaineers in Germany, Austria, and what is now the Czech Republic, until after 1920. The gourd-shaped design of carabiner became known as the "Feuerwehrkarabiner" ("fire brigade carabiner"), even if the specific carabiner was not in fact strong enough to be used by the fire brigades, and this confuses many sources into thinking that climbers were using actual fire brigade carabiners, which were much larger, heavier and stronger. It is likely that most carabiners that were used for climbing were originally made for the mining industry. The gourd-shaped design of carabiner is still commonly sold today for a variety of purposes, but almost never PPE rated. An 1888 design by American Edward A Wilson used a wire gate on a solid snap hook, possibly the first to do so. Previous designs had used the wire either just to make a spring, or as the gate, spring and hook at once. An 1889 design by American Winfred J. Smith had an inbuilt pulley for sliding along a rope or cable, exactly like many modern via ferrata cows tail carabiners. Much of the usage and development of carabiners within climbing took place in the Sächsische Schweiz mountains in eastern Germany and what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire (now northern Czech Republic), and was not publicised as much as in other regions. Surviving photographs from 1892 show climbers using gourd-shaped carabiners. They could be clipped to a piton and used as a pulley for hauling, or to connect a climber to a piton for safety, or as a descender. It is not known exactly which country would have used them first for each of these purposes, but most of the climbing took place on the German side of the border, and the Austro-Hungarian side of the border was, at the time, mostly populated by Sudeten Germans (German Bohemians), so either way, their usage is likely to be German in origin. An 1893 design by American Charles H. Smith had an S-shaped body, with two trigger clips. An 1896 design by German Otto Fechner had a captive eye for a rope at one end, and a hook with a sprung metal gate at the other end. A locking sleeve could be turned to sit over the lip of the gate. This was the first twist gate, but since it was not self closing, it functioned more like a screw gate, which needed only half a turn to engage. French arborists were using carabiners in 1896 to support themselves in trees. Their design was a smaller version of the much older type of fire brigade carabiners, with a captive eye. An 1897 design by Canadian Reuben C. Eldridge had an S-shaped body, with two separate gates, just like a modern S-carabiner. A supposedly tough 1897 captive eye design by American Albert Moritz had an inwards opening sprung gate, which was not load bearing or lockable.

C. Wissemann reported that climbers/mountaineers were using carabiners as a descender and to connect to ropes in 1898 in Germany/Austria, but good ones were hard to obtain in 1899. By 1902, the Austrian mining industry was using carabiners for many tasks, and the gourd-shaped design had been relaxed so that the sides were now almost straight. This was the precursor to the narrow pear-shaped design, and was depicted as being in use in what is now the Moravskoslezský Region of the Czech Republic, but was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire. German mountaineer Hans Leberle described how in 1903, he and two climbers identified as Bachschmid and Schneider had used carabiners on the Zugspitze on the border between Germany and Austria. No details of their use or design was given, but the article described them being used on days when they were not using ice axes, so presumably it was not just walking over glaciers, and the rest of the article talked very clearly about climbing. A 1904 oval design by Americans Joseph Eugene Borlaug and Julia Borlaug had an outwards opening gate with a spring loaded safety catch that kept it closed (very similar to an EDELRID Pure Slider lock), designed for snow chains. It did not have a sprung gate, and would not normally be considered to be a carabiner. Another 1904 design by American John Emil Johnson used a screw threaded sleeve over the gate, but with the screw sleeve on the body of the carabiner instead. The screw sleeve was in a different position on the body from where Luke Chapman had described as an alternative in 1883, because the depiction was of a spring hook where the hinge was placed at the opposite end of the gate. However, the text also described a standard carabiner, where Luke Chapman's patent would have had prior art. By 1908, gourd-shaped carabiners and captive eye versions, both with dovetail latches, were being used by the mining industry in areas that are now Germany, and were the most likely source of climbing carabiners. While the design was slightly more gourd-shaped than the Austrian version, it was not as extreme as it had been in the previous decades, and the whole industry was moving towards smoother curved designs. They still also used older designs, with visible compression springs for the gate, and without load bearing latches. The smaller carabiners were stated as being stronger than the larger ones, with the larger ones (which were popular with the fire brigades) failing to survive drop testing at a fall factor of 0.75 with a mass of 75 kg on a Manila hemp rope, while the smaller carabiners survived it. By that time, many German references called the older gourd-shaped design a "pear-shaped" carabiner, but it is quite different from what is now called a pear-shaped carabiner in English, and this confuses some sources into thinking that the narrow pear-shaped design emerged earlier than it actually did. Several 1909 designs by Germans Pick & Fleischner used the springing power of the carabiner's spine to make a gate lever stay open or closed, creating the first captive carabiner with a divided loop (similar to a Mammut Smart or DMM Belay Master). A 1909 design by American Frank E. Schartow was an S-carabiner where both gates opened at the same time, where the load pulled on a lever to keep the carabiner closed. A 1910 design by Thomas D. Owen used a wiregate with the now normal U-shaped construction latching onto a small nose, intended for use with horse tack. The springing power came from the wire, like a modern wiregate, but used the spring itself as the hinge instead of having a hinged joint. By July 1910, German climber/mountaineer Hans Dülfer was using carabiners as a belay device, presumably using a carabiner wrap.

German climber/mountaineer Otto "Rambo" Herzog is mistakenly credited with developing the first climber/mountaineer's carabiner in 1910-1911, after seeing carabiners on belts of the local München fire brigade uniform. However, while he did use carabiners, the majority of claims made about his contributions are incorrect, and the facts behind the myth are much less dramatic. So much nonsense is repeated about him in relation to this subject that it is hard to find the actual information, but it is highly unlikely that he ever designed or made any carabiners himself, since he was trained as a carpenter, not a blacksmith, and he never wrote about making one, and never patented anything. It is most likely that he simply bought carabiners and used them, and just in case it needed to be said, that does not count as an invention. He probably started using them in 1912 (a year before he used them for a climbing tension traverse), in spite of his peers complaining about climbers using artificial aids. The low quality carabiners he used were made from mild steel, and would sometimes open accidentally because they were weak enough to flex too much, being only just able to hold the weight of a person. Even though many sources like to show them as a narrow pear-shaped carabiner, it is almost certain that he first used a gourd-shaped design. That is the only design mentioned in climbing newsletters from Germany and Austria, the areas where he was climbing, until the 1920s. Although he was trying to immitate a fire brigade design, it is more likely that he used carabiners that were sold for utility purposes, rather than the larger types sold for the fire brigades. They were also not even slightly the first carabiner, or the first used by climbers, or the first modern shaped carabiners, or the first carabiners capable of holding a person, or the first modern rated carabiners. In fact, carabiners designed for holding a person had existed for 65 years at that point, and climbers/mountaineers had been using them for over 30 years. (Even if he had made them himself, the only thing he would have "invented" was the idea that a carabiner could be created by a climber/mountaineer, and subsequently be used by a climber/mountaineer, something which is not really an invention at all.)

Paul Preuss, one of the most vocal critics of aid climbing and the use of any artificial climbing aids, died in a serious fall in 1913, because he did not have adequate protection. Artificial aids suddenly became acceptable, and climbers started using carabiners more heavily. Like many other climbers before him, Otto "Rambo" Herzog had already insisted on using carabiners and was putting them to good use, and because of the lucky timing, many people now think he invented them. He didn't. The myth seems to have originally developed as a result of a 1939 second hand mention of when he had first used carabiners, in which it was never claimed that he invented them or was the first climber to use them. It simply said that by some time in 1912, he was "already using carabiners on an experimental basis". Congratulations, many other climbers had been doing so for decades. The myth then became established as a result of a 1968 article in Alpinismus written by Austrian mountaineer Toni Hiebeler, and translated into English in 1969. The article rightly points out that evidence suggests that others such as Hans Dülfer had already used carabiners, even though Otto "Rambo" Herzog had used them before Hans Dülfer's 1912 ascent of the Austrian Fleischbank (perhaps the article's wording confused people into thinking this happened before 1910). However, it failed to notice the 30 previous years of carabiner usage by climbers/mountaineers, which had been documented by the German and Austrian Alpine Association. Otto "Rambo" Herzog's climbing partner German Gustav Haber gave the origin story about carabiners being seen on fire brigade belts, and did not suggest that Otto "Rambo" Herzog had made any himself. Gustav Haber specifically stated that the fire brigade's gourd-shaped design was used (which he referred to as pear-shaped, like many Germans did at the time), and that as far as he knew, a fire brigade device had been used. The mistaken idea that Otto "Rambo" Herzog was the first to use them was created by people that he spoke to, who had not seen anyone else use them, and incorrectly assumed he was the first to do so. His own nephew was one of the people making the mistaken claim, which reinforced the myth. The myth then appeared in books in 1990.

It should be noted that what would later become Nazi sentiment was already very strong in southern Germany and Austria by the late 1800s. This was particularly noticeable within the various Alpine clubs, who after having adopted rules to exclude others very early on, went to great lengths in the early 1900s to erase records and rewrite history, making themselves appear to have been first for a lot of things that they were in fact not the first to do. This became an intentional government policy during the 1930s and 1940s, and it makes historical research quite difficult, as the books that proved otherwise may literally have been burned, and the historical record intentionally polluted. Another example of this is the development of the Prusik knot and its applications. Therefore, it is quite likely that the attempts to promote a southern German false hero as the first to use carabiners for climbing were done very intentionally, as they may not have been aware of the actual origin, or which ethnic group their climbing use originated in.

Climbers still like to claim that he invented carabiners over 400 years after they were actually invented, just because he was a climber, even though climbers were already using carabiners a decade before he was even born. By that measure, cavers should claim that a caver invented them because at least one caver actually made one many decades after cavers started using them, sailors should claim that a sailor invented them, the mining industry should claim that a mining engineer invented them, fire brigades should claim that a firefighter invented them, kite surfers and keyring makers should claim that ... well, you can see where this is going. Things get invented when they get invented, not when someone with a particular hobby makes one of them or uses one of them. The Messner Mountain Museum has an asymmetric offset triangular carabiner with curved corners, which they say was used by Otto "Rambo" Herzog and Austrian mountaineer Hans Fiechtl in 1920, a design which was used (but not popular) until the 1960s. Reinhold Messner, owner of the museum, stated (personal communication) that Otto "Rambo" Herzog had obtained their carabiner locally and used it for climbing, and had not designed it or made it himself. The suggestion was that this carabiner had been borrowed from a fire brigade workshop. However, it is not known if this design of carabiner was ever actually used by the fire brigades, and there is no evidence to show if the actual source of the carabiner had anything to do with the fire brigades, or whether this is simply another version of the myth. There is also no known evidence that Otto "Rambo" Herzog ever used it, or that it existed in 1920, since this design was only recorded in the 1930s. (Hans Fiechtl did actually design metal pitons and have them made by a local blacksmith, but their manufacturing quality was far too low for him to have been the source of the earlier carabiners.)

In 1920, the use of carabiners for climbing was described in detail in a German and Austrian climbing newsletter article called "Das Versichern beim Klettern" by mountaineer Hermann Amanshauser, based in Salzburg, Austria, very close to München in Germany. (He ran a mountaineering shop aimed at skiing in 1926, and taught skiing and climbing to young mountaineers, but seems to have become better known as a Nazi SS officer and skiing instructor before and during World War II.) As well being as the earliest widely distributed climbing publication to describe the complete approach of using carabiners attached to pitons, and running ropes through them for safety while belaying as they are still used today, it also described them as being used as a belay device, using a carabiner wrap. Gourd-shaped carabiners were shown as being 10.5 cm long, using metal that was 10 mm thick, referred to as a "so-called fire brigade carabiner". The article stated that the gourd-shaped carabiners were very suitable, but "oval" carabiners were better, though it did not say whether this referred to a modern oval, a narrow pear shape, or an elliptical carabiner.

Elliptical carabiners (curved all the way around) with a load bearing dovetail latch were shown in German mountaineer Franz Nieberl's book Das Klettern im Fels in 1921, published in München. However, they were very weak due to the way the curve could load the gate. In earlier decades, the gourd-shaped design had been the most popular, but by 1921, Franz Nieberl referred to it as the "previously used shape". The same book showed narrow pear-shaped carabiners with a dovetail latch, and this is the first time they are conclusively shown in relation to climbing, stated as being less likely to trap the rope than the gourd-shaped design. Presumably they had started to be used for climbing either in 1921, or they might be the "oval" design referred to in 1920. These narrow pear-shaped carabiners are almost exactly the same as the mining design used in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1902, with the only difference being that the sides were straight or slightly bent outwards instead of inwards. This difference might not have been intentional, and could just as easily have been because a different company was making them, or a different manufacturing machine was being used to bend them into shape, because of the stronger steel and load bearing latch which the 1902 version did not have. Surviving examples have sides that bend inwards or outwards, due to inconsistencies in their manufacture. The publications did not give the source, but many sources stated that climbers were buying their other metal hardware in hardware shops, not specifically made for climbing (with the exception of pitons). Das Klettern im Fels explicitly stated that the carabiners were smaller than the versions used by the fire brigades, so the fire brigades were not the source, but that they were finely crafted from the best forged steel, with extremely well made gates. They are therefore likely to have come from a major industry with excellent production methods, likely to have been the mining industry. German references subsequently called the narrow pear-shaped design an "oval" or "round" carabiner, since it is actually oval (like an egg), unlike what would currently be called oval. It is no longer used for carabiners, but this shape is still used for some maillons.

Many modern sources state that the narrow pear-shaped carabiners weighed 130 grams, but they are simply copying each other without checking actual carabiners. This number seems to have originated in Toni Hiebeler's article, which blindly stated that all previous carabiners used for climbing before 1939 had weighed 130 grams, which is clearly nonsense, since they were available in multiple sizes, using different thicknesses and different designs. In 1922, Anwendung des Seiles showed three designs of carabiners. The gourd-shaped design was referred to as a "Feuerwehrkarabiner" meaning "fire brigade carabiner", while the other two designs had no name, and all three were called "Karabiner". The second design was the narrow pear-shaped design, which was stated to be better than the gourd-shaped design, because the gourd-shaped design could accidentally trap the rope at the narrower end. It was described as a new design, between 10 and 12 cm long, and since this booklet was published in the same city as Das Klettern im Fels, it suggests that the design had not been used for climbing in that area until about 1920. Alongside those was an oval carabiner with identical half-circle ends and straight sides, just like a modern oval carabiner. It was very clearly drawn, with a load bearing dovetail latch. Its purpose was stated as being used for glacier crossings, using the method described by Carl Seitz, or clipping to a piton for safety. Both the narrow pear-shaped design and modern oval design were shown being used for catching climbing falls.

German climber August Schuster ran an alpine sports company in München called Sporthaus Schuster, which still exists. In the summer of 1924, Sporthaus Schuster was selling modern oval shaped carabiners, which they simply called a "Karabiner". (Toni Hiebeler's article mistakenly said this was in 1921 and cost DM 7.50, but it was actually in 1924 and cost just DM 0.70.) This was stated as being made with nickel, so it was presumably nickel plated steel, and had a load bearing dovetail latch. It was featured in the same section as pitons, so it was intended to be used for climbing. This is the first known commercial sale of any carabiner for this purpose, but it is highly unlikely that they were being specifically made for climbing, and were probably just rebranded as climbing carabiners. They were probably sourced from mining manufacturers or general hardware manufacturers, but they did not have any branding to show the origin. The Sporthaus Schuster catalogues show that they started to use the "Shuster" branding on their own custom made products from the winter of 1924-1925 and the ASMü branding in the early part of 1925, but their carabiners remained unbranded, which suggests they were never specifically made either for climbing or for Sporthaus Schuster. Also in 1924, the modern oval design was depicted being used for climbing in the same region by Ernst Platz. In 1925, Sporthaus Schuster started calling carabiners "Seilkarabiner", meaning "rope carabiner", and started selling the narrow pear-shaped carabiner in addition to the modern oval carabiner. In 1926, Anwendung des Seiles again showed the same designs of carabiners, but none were shown in relation to crossing glaciers. Stronger steels started being used in the 1920s, and carabiners were then considered more reliable, though they could still only be trusted to catch shorter falls. The earliest known D-ring carabiner was made at some point during the 1920s, but its origin is unknown. The gourd-shaped designs remained in use by climbers until the late 1920s.

When carabiners started to be used for climbing in English speaking countries, climbers forgot that they had already existed in those countries for centuries, with no less than 4 English names already. Instead, they acted like they were a new invention, and called them by the incorrectly shortened version of their German name, a mistake which has endured for the last hundred years, and even made its way back into German in industries that had previously used the correct name. Carabiners were mentioned in English literature from the late 1920s, with "carabiner" being 2-4 times as common as "karabiner" until the early 1950s. A 1927 design by American Ernest J Shaffer was an S-carabiner with single wire gates, similar to some modern carabiners like the Petzl Ange. By 1928, the narrow pear-shaped design was being sold in Sporthaus Jungborn in Dresden, near the Sächsische Schweiz mountains. By 1929, both the modern oval and narrow pear-shaped designs were being sold by Mizzi Langer in Vienna, and they were called "round oval" and "pointed oval" respectively, names which would be adopted by Sporthaus Schuster by 1934. In 1930, modern oval carabiners were depicted again in Anwendung des Seiles. They were referred to as "round", with the narrow pear-shaped carabiners now being called pear-shaped in German. The narrow pear-shaped design was still preferred because it made it easier to see the gate. Both were available in smaller and larger sizes, with the smaller size being normally preferred. During the 1930s, they became very popular for climbing, and the strength soon reached around 1 tonne. The modern oval design became the main one used for climbing during the 1930s, and carabiners of this design are still used for caving today. They are also a very common design used in rope access, and many rope access devices are designed to be used only with oval carabiners.